Steve Kerr’s Life Story was Worth Writing, and it’s Worth Reading

Steve Kerr: A Life

By Scott Howard-Cooper

William Morrow Publisher

Scott Howard-Cooper had it all set up.

The veteran Sacramento journalist was prepared to write a book about the Golden State Warriors’ fourth NBA championship in five years in 2019. That plan went awry when the Warriors fell to Toronto in six games in the Finals.

“We were screwed,” Howard-Cooper says. “Nobody wanted to read a Warriors book coming off a loss.”

Howard-Cooper’s literary agent, Tim Hays, had another idea.

“He encouraged me to write a book on (Warriors coach) Steve Kerr,” Howard-Cooper says. “He stayed on me. He said, ‘Write out a proposal. Take a little time and put something on paper.’

“He was not only right, he was very right. It went from me thinking I didn’t want to do it, to one day saying, ’No one has done this before (written Kerr’s life story). I’m going to do it.”

The result is “Steve Kerr: A Life,” scheduled for a June 15 release.

I received an early review copy and was thoroughly entertained reading about one of my favorite people in pro sports, written by a talented scribe whom I’ve known for 30 years.

The book is unauthorized. Not that Howard-Cooper didn’t try to get Kerr — the long-time NBA sharpshooter during his playing days who coached the Warriors to three NBA titles — to cooperate.

“I went down that path with Steve,” says Howard-Cooper, 58, a former writer with the Los Angeles Times, Sacramento Bee and NBA.com. “We had an email exchange. I made my case. His response was polite but definite: ‘I wish you luck. Nothing personal. I have zero interest.’ ”

One of Kerr’s mentors, Spurs coach Gregg Popovich, helped convince him that writing an autobiography while still coaching would be a mistake, that his players would consider it a “glory grab.”

“A lot of people say it’s Steve avoiding publicity,” Howard-Cooper says. “That part is true. He wanted no part of it, but he made it clear it was nothing personal. Pop had told him, ‘As soon as the players see you making it about yourself, you risk losing the locker room.’ I would counter that if Steve Kerr doesn’t have the locker room after all he has accomplished, nobody ever will. But it still worked out OK.”

Howard-Cooper, however, encountered obstacles. The entire Golden State organization fell in line and declared itself off-limits to anything beyond the access available to all. Family and some friends declined to cooperate, too. Others spoke only on condition of anonymity, even though Howard-Cooper’s book was intended to be anything but a hatchet job about a likable, wildly successful sports personality.

(Scott got in a great one-liner on that subject in the book: “The Warriors are to be commended for taking a firm stand against positive publicity.”)

How much did the author miss by not getting one-on-one time with the book subject and so many close to him?

“A little bit,” Howard-Cooper says. “It would have helped. I don’t deny that. But it was not a major setback.”

It still worked, he contends, in part because “I feel fluent in Kerr.”

“Steve was hoping he’d put an end to the project before it started,” Howard-Cooper says. “He was surprised I was still moving forward. But I had plenty of access to his 40 years in the spotlight. He has done thousands of interviews, a lot of them in-depth. I was involved in hundreds of hours of interviews with Steve myself and in group settings, and dozens of hours since he has been with the Warriors. I’ve been to every NBA arena he played in and every Pac-10 gym he played in.

“I’ve spent hundreds of hours around Steve through the years. I’ve been around the Warriors hundreds of days. I first interviewed Steve in college. I felt very comfortable with the subject. The things I’d have liked to have asked him were nothing controversial. They would have been about personality, like, ‘Take me through this certain moment,’ to flush out certain areas. That would have been helpful.”

Howard-Cooper still interviewed 125 people for the book, most of them one-on-one, about a man almost universally beloved.

“In 40 years around professional and major-college sports,” he writes, “I have never heard people talk about someone the way they talk about Kerr.”

Howard-Cooper had access in group situations to Kerr, whom he says answered his questions willingly and in detail. The result was plenty of insight to the man who has eight NBA championship rings — five as a player with Chicago and San Antonio, three as a coach with the Warriors.

Kerr qualifies as a great subject for a book. He was always the underdog through his playing career: Few college options coming out of high school in Pacific Palisades, Calif., until a late scholarship offer from Arizona, the 50th pick in the second round of the draft (to the Phoenix Suns in the 1988 draft). The questions continued through his NBA career: Could he make a team? (He played 15 seasons.) Could he ever be a useful player? (He is the all-time career 3-point percentage leader.) Could he help a team be a winner? (He was a regular contributor and was the hero of one of the Bulls’ titles with a series-winning 3.)

The advantage of an unauthorized book is the author has the freedom to paint a more honest picture of the protagonist. Kerr was no goody two-shoes, and Howard-Cooper doesn’t sugar-coat things. He tells about Kerr’s troubles as a general manager in Phoenix. Kerr has imbibed in his share of alcohol (he once got hammered with Dennis Rodman to “nurse Rodman’s spirits” as a favor to coach Phil Jackson), issued his share of salty language and exhibited some temper at times. But Kerr’s good mind, spirit and heart is on full display, and Howard-Cooper’s smart writing makes it sing.

In describing why unpopular Bulls GM Jerry Krause called him “OKP” — our kind of people: “Bouncy Kerr, with his breezy, genial personality, may have been the antithesis of (Krause) alienating the roster and cloaking the front office in secrecy, and Kerr would never be a suck-up genuflecting before the personnel boss, but Kerr had been a company man every stop in his career. He filled enough other requirements to be a proper Bull worthy of an acronym.”

Kerr’s coaching credentials before taking over the Warriors in 2014 provided a much different portfolio from his own coaches, men such as Lute Olson, Cotton Fitzsimmons, Phil Jackson and Gregg Popovich, “the latter with eight years as head coach at Pomona-Pitzer, a small university in Southern California, and runs as an assistant at Air Force, Kansas, Golden State and San Antonio. Kerr had instincts and a Word doc.”

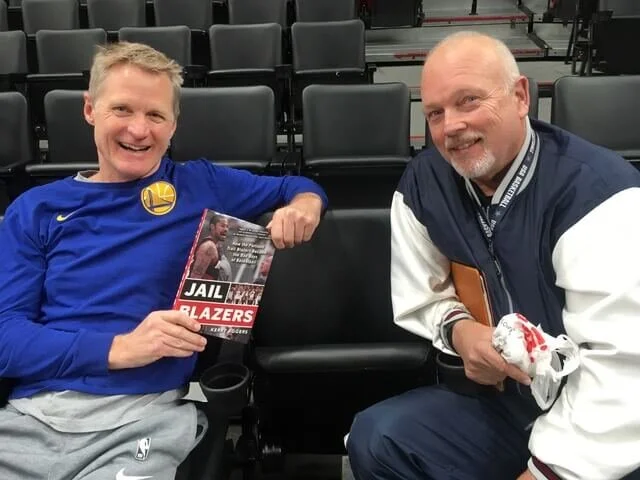

I got to know Kerr reasonably well during his one season in Portland — 2001-02 — in the heart of the “Jail Blazer” era. Howard-Cooper treads lightly on that subject, but offered this in our conversation about the book:

“Portland was an interesting time in Steve’s life. That time ended up shaping him quite a bit. You really began to see that this guy would be a coach. There was a foreshadowing of what he would become. Steve connected with all of his teammates. Relationship-building has become a huge part of him as a coach. That’s what you saw in Portland.”

Howard-Cooper also writes that then-Blazers president Larry Miller made Kerr a primary target to hire as GM in May 2011, then made another run at him 11 months later when the job reopened. This was after Rich Cho was fired and after his replacement on an interim basis, Chad Buchanan, wasn’t rehired. Kerr turned down the offer both times.

What I think Howard-Cooper may have missed most due to lack of access was Kerr’s in-depth perspective on a collection of former teammates who include Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Shaquille O’Neal, Tim Duncan and David Robinson. Howard-Cooper touches on each, but more reflection would have been helped.

The author, though, does a nice job of conveying Kerr’s dry wit and clever sense of humor. During what would become a nightmarish, injury-ravaged 2019-20 season, he asked NBA commissioner Adam Silver if the Warriors could skip the season “as a sabbatical. Maybe go to Italy, ride bikes and sip wine. Take the year off.”

The Warriors finished 15-50 during the regular season, which caused Howard-Cooper to write this final line to the book: “At the end of 2020, Steve Kerr again found himself with something to prove.”

So the timing may have been bad, but the product wasn’t.

“I had a lot of fun doing it,” Howard-Cooper says. “I hope that comes through.”

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.