You can skip reading this book by Traitor Bob

Updated 1/28/2024 9:45 AM

(To make it easy for you to buy any of these books if you are interested, I made each image linked to buying the book right on amazon.com or bookshop.org. I do get a commission if you use the links in this post.)

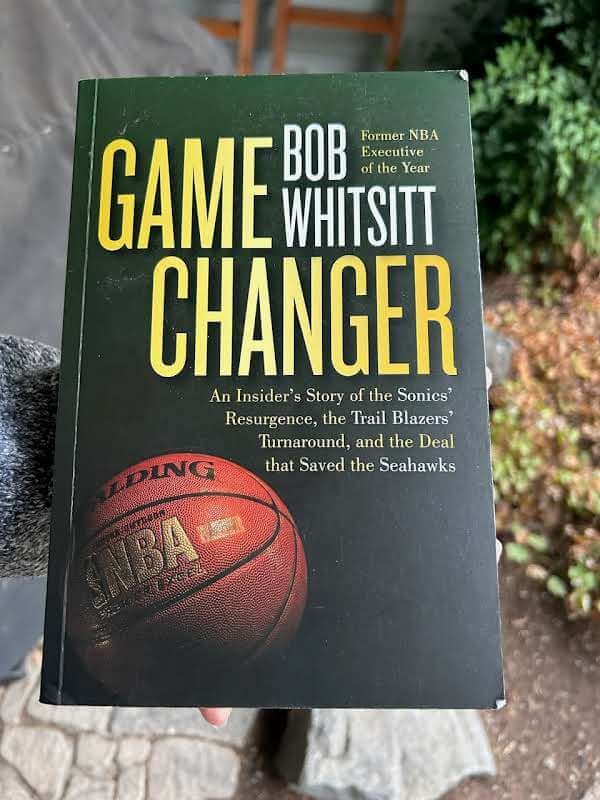

By Bob Whitsitt

Flash Point Books

For more than a decade, Bob Whitsitt was the curator for Paul Allen in running both the Trail Blazers and the Seattle Seahawks.

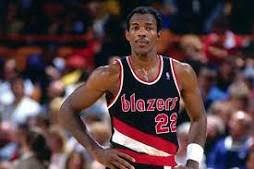

Or as Clyde Drexler calls it, “Paul’s henchman.”

From 1994-2003, Whitsitt was president/general manager of Portland’s NBA franchise, presiding over what came to be known as the “Jail Blazers” era.

Whitsitt also served as president of the Seahawks from 1997-2005, drawing the ire of coaches Dennis Erickson and Mike Holmgren during his time running the NFL club.

Now Whitsitt has come out with his autobiography, which he has shaped as a primer for an aspiring professional sports general manager.

In reality, it’s an exercise in shameless self-promotion and aggrandizement by a man who burned plenty of bridges throughout his career in sports management.

Whitsitt won the NBA Executive of the Year Award once — in 1993-94, when his Seattle SuperSonics finished the regular-season at 63-19. Seattle was promptly upset by the Denver Nuggets in the first round of the playoffs — the first time a No. 8 seed had beaten a No. 1 seed in NBA history.

“Trader Bob,” as he likes to call himself, largely constructed the roster of the 1995-96 Sonics, who lost to the Chicago Bulls in the NBA Finals. But Whitsitt was two years removed from that Seattle team. In 17 years as a GM, Whitsitt’s teams never made the Finals.

Throughout the book, Whitsitt — who turned 68 on Jan. 10 — stretches the truth, tells half-lies and makes boasts about himself, assessments that should only be delivered by others.

“I was the first one in the office every day and the last one to leave,” writes Whitsitt, who started his career in the NBA at age 24 with a three-month internship with Indiana Pacers.

Later, when Whitsitt enrolled in law school and got his degree at age 61: “I’ve always done well in school, not because I’m the smartest guy in the room, but because no one works harder.”

Whitsitt writes that one of the reasons he became a successful NBA executive was because “I’ve always been a good listener.”

He claims while attending NBA meetings for the Pacers an intern, he helped convince owners to institute the 3-point shot and do away with three-to-make-two at the free throw line.

Whitsitt trumpets his own playing career and athleticism. He says he played freshman basketball, four years of baseball and one year of football at Wisconsin-Stevens Point. During his one year on the gridiron, “I started out as 10th-string tight end but started the opener,” he writes.

When he was with Indiana, Whitsitt says he was thrown into scrimmages during practice sessions when the roster was depleted by illness and/or injury.

Writes Whitsitt: “At 6-3 and 200, I was probably the only guy on staff who had the size and athleticism not to get killed in a scrimmage with NBA players. … I loved the game and stayed in shape and kept my basketball skills sharp by playing in some pretty competitive city leagues.”

A few years later, when he was working for the Kansas City Kings, Whitsitt says he played in a semipro league with Ed Nealy. “I held my own usually scoring 10 or 12 points a game, mostly 3-pointers,” he writes. In a game against a team featuring Joe C. Meriweather and Larry Drew, “I lobbed a teardrop so high I thought it would be an air ball. When the floater swished, Meriweather chuckled and shook his head. ‘Damn boss. Not bad!’ ”

In his early 30s in Seattle, Whitsitt writes, he got called into duty for a two-on-two game involving draft prospects Olden Polynice and Derrick McKey. We get it, Bob. You were a stud.

As point man for the Kings’ relocation from Kansas City to Sacramento, “Not a day passed when I wasn’t making a speech to a civic or community group or a potential team sponsor, not to mention never-ending requests for media interviews,” Whitsitt writes.

Whitsitt was hired as president and GM of Sonics in 1986 at age 31.

“I’d never met anyone my age who had anywhere close to the depth and breadth of experience I had gained in the first eight years of my career,” he writes. “I was driven and disciplined and had lots of hands-on knowledge about the inner workings of struggling NBA franchises, which gave me the confidence to go about transforming the Sonics.”

The Sonics were a “train wreck” when he got there, he writes (they had gone 31-51 the previous season). He paints himself as a draft and trade genius, landing Shawn Kemp (with no college experience) at No. 17 and Nate McMillan in the second round. He traded aging Jack Sikma to Milwaukee for Alton Lister and future first-round picks that became Kemp and McKey. The Sonics got to the Western Conference finals in his first season (1986-87).

Whitsitt brags about putting one over on opposing GMs such as Milwaukee’s Del Harris (trading Dale Ellis for Ricky Pierce) and John Nash and hoodwinking Nets GM Willis Reed into thinking the Nets needed a big man (Derrick Coleman) with the first pick in the 1990 draft, opening the door for the Sonics to draft Gary Payton at No. 2.

When he came to Seattle, Whitsitt writes, “I had started with a lousy team, with no salary-cap space, no draft pick, and had built them into a championship-caliber powerhouse with not only the best record in the NBA but an abundance of salary-cap space and a lottery pick because of a trade I’d made the year before.”

► ◄

The middle part of the book is about Whitsitt’s near-decade with Portland, which will hold the most interest to Blazer fans. He makes plenty of assertions that can only be confirmed or refuted by Allen, who died of cancer in 2018. He also made plenty of statements about Drexler and Mike Dunleavy, the latter the Blazers’ coach from 1997-2001. Both of them are still alive.

Whitsitt arrived in 1994 after P.J. Carlesimo was hired as coach following Rick Adelman and the Clyde Drexler/Terry Porter regime. Over the next couple of years, Whitsitt got rid of all the parts of the nucleus that reached the NBA Finals twice in the early ‘90s. Whitsitt claims he never had a chance with the Blazer fans.

Writes Whitsitt: “Portland fans and the media were already seething that their team’s Seattle owner had not only just hired another Seattle guy to be the Blazers’ GM — but the guy who had just left the Sonics? They welcomed me about as warmly as a fox would be greeted at the door of a henhouse.”

Maybe they resented the fact that Whitsitt never lived in Portland. He rented an apartment and kept his residence in Seattle. “My office is my cell phone,” he would say. “I can live anywhere.” But he never was able to feel the pulse of the city in which he was working. He was mostly oblivious to what created the love affair between fans and the team that had become “Blazermania” through the previous two decades.

Whitsitt says among his first duties with Portland were to address Drexler’s money wishes, then to trade him.

Writes Whitsitt: “Paul told me, ‘I think I promised Clyde Drexler another contract extension, but under no circumstances am I giving him more money. And you’ve got to be the guy to get me out of that.’ ”

Soon thereafter, Whitsitt says, Drexler went into his office and asked for a trade.

“At first, Clyde wanted to go to a bad team, thinking he could command more money,” Whitsitt writes. “I saw things differently. I wanted to trade him to a team where he could be the difference-maker and win a championship.

“I said, ‘Clyde, believe me. All you care about is money right now, but when it’s all over, you’ll be happy you won a championship elsewhere.’ ”

Whitsitt all but gave away Drexler at the trade deadline in 1995, getting back a first-round pick and veteran forward Otis Thorpe, who played 34 games for the Blazers before being moved to Detroit with the pick in the offseason.

When I called Drexler for a reaction, I got plenty.

Hall of Famer Clyde Drexler calls Bob Whitsitt “the most arrogant jerk to come through Portland”

“It’s malarkey,” Clyde told me. “It was quite the opposite. I was the one who wanted to go to a contender. If I can’t compete for a championship, I’m not playing. Why would I want to go to a bad team? That makes no sense.

“For him to say I’d go to his office is an absolute lie. Why would I speak to him? Paul and I talked all the time. If there was anything Blazer-related to discuss, I talked to Paul. I don’t recall ever having a conversation with Bob, except toward the end, when I told him there’s only one place I would go, which was Houston. That was it.”

Clyde wasn’t finished.

“I thought they busted up the team too soon,” he said. “We still had a championship-caliber roster. After he hired Whitsitt, I called Paul. I said, ‘If you’re going to be rebuilding, do me a favor, I’m not interested. I would retire first. Trade me.’

“Paul said, ‘If I do trade you, it’ll only be because you asked me to.’ My relationship with Paul was excellent. But Bob was brought in to be the henchman, to get rid of veterans and start over. Given his reputation from Seattle, we knew he was that guy. I don’t think anybody was mad about it. If the owner wanted to start over, that’s his prerogative. But nobody liked Bob. We all knew what he was doing. He’d come into the gym and guys would go the other way.

“Guys couldn’t stand him. He had no people skills — zero. Our whole franchise was based on communication and collaboration. That’s a big part of the reason why we were good. Then this guy comes in and is as straight-ass arrogant as the day is long. Nobody liked that dude. And now he is writing this book, trying to make himself out to be bigger than he was.”

Drexler was offended by one other sentence in Whitsitt’s book: “Then there was Marshall Glickman, son of Blazers founder Harry Glickman, who ran the business side of the franchise; no one liked him.”

“I thought Marshall was a great guy,” Drexler says. “The whole city liked the Glickmans. That was Blazer family — Jenny (Marshall’s sister), Marshall and Harry. Whitsitt was the most arrogant jerk to come through Portland.”

► ◄

Over his first eight years with Portland, Whitsitt brought in the likes of J.R. Rider, Rasheed Wallace, Bonzi Wells, Gary Trent, Ruben Patterson, Zach Randolph and Qyntel Woods. Their talent was palpable but their behavioral issues were widespread, creating embarrassment in the community in which they were playing.

In his book, Whitsitt lays it all on Allen.

Writes Whitsitt: “Paul made it clear to me that he wanted me to build a winning team without worrying about player image problems. ‘We’ve got to be willing to bring in the bad boys,’ he said. ‘I think you can manage the bad boys, Bob.’

“This was well before people started calling us ‘the Jail Blazers,’ suggesting I was deliberately ignoring the checkered pasts of players I added to the roster. In reality, I carefully considered each player’s strengths and weaknesses, the assets they’d bring to the team, the liabilities that might get them in trouble and everything in between. Ultimately, a GM’s job is to assemble the kind of team the franchise owner wants. Paul wanted young, raw, explosive talent and was not only willing to take risks on players with ‘bad boy’ reputations, but welcomed it.”

No player came with more baggage than Patterson, to whom Whitsitt bestowed a six-year, $34 million contract in 2001. The previous May, Patterson had entered a modified guilty plea to third-degree attempted rape by forcing the family nanny to perform oral sex on him. With the guilty plea, he was ordered to register as a sex offender and the NBA suspended him for the first five games of the 2001-02 season.

That wasn’t all. In February of that year, Patterson was convicted of misdemeanor assault for attacking a man outside a Cleveland nightclub. After his first year in Portland, Patterson was arrested for felony domestic abuse charges on his wife. She later dropped the charges but they divorced.

Patterson had problems during his two years at the University of Cincinnati, too, including an aggravated burglary arrest and a 14-game NCAA suspension for extra-benefit violations.

At the time Patterson signed with Portland, Danny Ainge was head coach of the Phoenix Suns.

“There was a red flag on Ruben,” Ainge said then. “I don’t know where you draw the line. That is up to the owner of the team. Whatever image you want your team to display, if you want to win at all costs … those are the choices Paul Allen has to make. Ruben was on the list of many teams, but most chose not to pursue him.”

Whitsitt at the time: “It is something I take very seriously. We are very concerned with some of his issues off the court. We spent a great deal of time talking to people who have coached Ruben who have known him for a long time, who have played with him.”

Patterson isn’t mentioned in Whitsitt’s book. Rider gets a few paragraphs. Whitsitt describes an incident where Rider got upset at a heckler and left the arena before the end of the game. Rider ultimately got a 10-game suspension.

“Ultimately, I think J.R. respected my follow-through,” Whitsitt writes. “It’s how I got the most out of him during his three years with the Blazers. … rules never applied to him until he got to Portland.”

Whitsitt gave up James “Hollywood” Robinson, Bill Curley and a first-round draft pick in the trade that brought Rider from Minnesota in 1996.

“The Timberwolves were itching to get rid of J.R.,” Whitsitt writes. “Where they saw deal-breaking distractions, I saw untamed immaturity that could be reined in with guidance and discipline.”

Yet later, Whitsitt writes about how one of the best trades he ever made was sending Rider to Atlanta for Steve Smith. “It was my master chess move,” he brags. “I took a player no one wanted, invested in his development, got his best basketball out of him, then traded him for a quintessential good guy who was one of Atlanta’s most popular players.”

(To detail all of Rider’s misdeeds as a Blazer, see my book “Jail Blazers”).

► ◄

Whitsitt goes relatively easy on Carlesimo, who lasted three seasons with the Blazers before being fired. Not so on Dunleavy, who took over in 1997 and made it through four seasons before he was fired in 2001.

Former Blazer coach Mike Dunleavy disputes much of what Bob Whitsitt writes

Dunleavy was NBA Coach of the Year in the lockout-shortened 1999 season, during which the Blazers went 35-15 in the regular season and lost to San Antonio in the Western Conference finals. He coached the 1999-2000 team that went 59-23 in the regular season — second only to the Lakers’ 67-15 — and lost in seven games to the Lakers in that unforgettable West finals. Blazer fans don’t need to be reminded that their team led by 15 points late in the third quarter of Game 7, then floundered in a fatal fourth period in a heartbreaking 89-84 loss.

“To this day, I’m convinced that was the best NBA team that didn’t win a championship,” Whitsitt writes. “After losing to the Lakers, Paul wanted to fire Dunleavy. We agreed his coaching mistakes early on in the series had arguably cost us the championship. But … I pushed back. I’ve always erred on the side of loyalty with my coaches. I respect what a hard job they have. I talked Paul into giving Mike another year. In hindsight, I shouldn’t have.”

The Blazers were loaded at center and power forward, with Arvydas Sabonis, Wallace, Brian Grant, Detlef Schrempf and Jermaine O’Neal, then 21 and in his fourth NBA season.

O’Neal was buried on the depth chart and unhappy about it.

“Jermaine would often come into my office in tears, complaining about how little he was playing,” Whitsitt writes.

O’Neal’s initial three-year contract had ended with the 1999 season. Allen, Whitsitt writes, wanted to re-sign him “at all costs.”

Writes Whitsitt: “I said, ‘Paul, that’s going to be tough.’ I leveled with him. ‘The kid hates Mike Dunleavy, and Mike hates him.’ Paul wanted me to fire Dunleavy, but I pushed back.”

Whitsitt writes that during that offseason, he spoke with Dunleavy and emphasized he needed to tell O’Neal he was going to play “10 to 15 minutes a game most of the time, if he earns the minutes.” He writes that Dunleavy joined him in visiting O’Neal in his hometown of Columbia, S.C.

Writes Whitsitt: “As I pitched Jermaine on the advantages of staying in Portland, I turned to Mike and said, ‘Hey Coach. Why don’t you explain to Jermaine how you see his role next year?’ Mike told Jermaine, ‘I’m pretty sure about two-thirds of the games will be matchups that I could probably get you about 10 to 12 minutes if you’re playing really well. But no guarantees.”

“I couldn’t believe it,” Whitsitt writes. “And at the same time, I wasn’t surprised.”

Even so, O’Neal signed a four-year extension worth $24 million, with what Whitsitt says was a promise that he would trade him if his playing time didn’t increase.

Again during the 1999-2000 season, Whitsitt writes that he told Dunleavy that he needed to play O’Neal five minutes in the first half of every game, and if he played well, play him at least another five in the second half.

“Mike agreed to do it but would never follow through, which infuriated Paul Allen,” Whitsitt writes. “Paul questioned whether I’d been clear enough, so we set up a meeting — Mike, Paul and me. I restated the minimum five minutes Jermaine was supposed to get in each half. Once again, Mike said he’d do it. But it made no difference. Jermaine kept warming the bench.”

I called Dunleavy for his version of the story.

“First of all, I didn’t hate Jermaine O’Neal,” Dunleavy told me. “I loved him. I did go to see Jermaine in South Carolina that summer, but not with Whitsitt. I went with Coach (Tim) Grgurich and (strength and conditioning coach) Bobby Medina. I had a conversation with Jermaine. I said, ‘We’re offering you a lot of money. It’s going to happen for you. Do you want to have your time guaranteed or do you want to earn the time?’ He said, ‘Earn the time.’

“During that next season, I did have conversations about Jermaine with Bob. I wanted to play him. But my point was, you expect me to win every single game. Five minutes a game doesn’t sound like much, but in tight games, it can make a difference. And he had two All-Stars playing in front of him. I was very careful to never promise anything.”

In August 2001, Whitsitt made a pair of blockbuster trades that altered the future of the Blazers. He sent Grant— a free agent — to Miami in a three-way deal that brought Shawn Kemp to Portland. A day later, Whitsitt traded O’Neil to Indiana for veteran power forward Dale Davis.

“I wanted to make sure the coach was on board (with the Kemp acquisition), so I had Dunleavy fly to Las Vegas, where Shawn was living in the off-season, and watch him work out,” Whitsitt writes. “In short order, Dunleavy sent Paul an email saying Shawn would work great as a backup center.”

Whitsitt writes he felt he had no choice but to trade O’Neal:

“Dunleavy had his sights set on Dale Davis. I felt terrible trading such a young player with so much potential, but we were well-positioned to make another run for the NBA title, so I supported the coach and traded O’Neal to Indiana for Davis. I’m sure some GMs would’ve had no trouble telling Jermaine, ‘Too bad. We’ve got you for three more years.’ But when I make a commitment, I always honor it. I lived up to my end of the deal, as disappointing as it was.”

On O’Neal, Whitsitt added, “All he’d needed in Portland was the playing time that Dunleavy had refused to give him.”

During Dunleavy’s final season with Portland (2000-01), the team’s depth was staggering. Twelve players averaged at least 14 minutes and most of them thought they deserved more. The Blazers started the regular season 42-18 — tied for best in the West — but were 8-14 over the final 22 games, finishing fourth in the conference.

Writes Whitsitt: “Dunleavy blamed everybody except himself for our struggles. In one interview, he claimed he’d had no idea we were trading Brian Grant for Shawn Kemp until his son had heard the news on the radio. The players knew Mike was lying and only looking out for himself.”

Whitsitt writes that Allen called him “in disbelief.”

“Do you think Mike has amnesia and forgot he told me he wanted Kemp?” Whitsitt says Allen asked.

Writes Whitsitt: “No. This is Mike trying to make himself look as good as possible.”

Dunleavy disputes most of Whitsitt’s account.

“I never asked for Dale Davis in my whole life,” Dunleavy says. “I didn’t even know there was a trade until the deal was done. The first thing I knew about it was when Bob tells me we’re getting Kemp for Brian Grant, and that he’s trading Jermaine and we’re getting back Dale Davis.

“I never signed off on Shawn Kemp. I said, ‘Dude, are you crazy? Kemp weighs 325 pounds.’ There was no reason to trade either Brian Grant or Jermaine O’Neal. Brian was our energizer bunny. Jermaine was not a free agent. He was under contract for three more years and we were paying more than anybody would have had at the time.

“Bob traded Jermaine without even consulting me. He said, ‘You’re forcing me to do this.’ I said, ‘I believe in Jermaine. Sabonis was a great player but is getting older. In two years, he’s outta there and Jermaine is playing 40 minutes a game. Bob, don’t do it.’ He said, ‘The deal is done.’ I said, ‘You’re out of your mind. We just went seven games with the Lakers in the conference finals. We’re going to be a threat to win it all the next season.

Why would I want those guys traded?’

“Bob was willing to sabotage his owner by making a trade because (O’Neal’s) agent isn’t happy with his playing time. Sabotage the future of the franchise to trade a guy? It probably never happened before or since in the history of sport. My mandate was to win every game. I tried to the best of my ability to do it. Bob made the deal that cost the franchise 10 years of being good in the future.”

Dunleavy says Whitsitt was always around when there was communication with the owner.

“In the years I was with the Trail Blazers, the only time I was ever alone with Paul was once in the summer league,” Dunleavy says. “He was eating a hot dog and we talked for about 30 minutes. He never sat down and asked me questions, ever. I never had that happen.

“But after the fact, after I’d been fired, Paul contacted me and asked, “Is it true you were not on board with Jermaine being traded?”

Dunleavy relates another story regarding O’Neal and Whitsitt:

“We’re near the end of a practice before a playoff game. I tell the players, ‘Everybody make 100 free throws and record (how many shots it took to get to 100). Jermaine left the playing floor. I saw it. I told somebody to go in and check with Jermaine and see if he shot his free throws. He came back and said Jermaine had to go pick up his girlfriend from the airport. I said, ‘That’s not the way this thing works.’ I fine him. He goes to Bob. Bob rescinds the fine. There were a number of times where Bob undermined me in that type of situation with players.”

Davis wound up being a solid player for the Blazers, but O’Neal blossomed into a seven-time NBA All-Star for the Pacers. Grant had four productive seasons with the Heat before injuries — and the beginnings of Parkinson’s Disease — began to take its toll. Kemp, meanwhile, was near the end of a stellar career in which he was a six-time All-Star. He was bloated and struggled with addiction in his two seasons with the Blazers — the first in Dunleavy’s final season as coach.

“I met with Paul and Bob that year about Shawn,” Dunleavy says. “I was playing him about 16 minutes a game to that point. They gave me an edict. They said it needed to be 28 minutes or it’s a fireable offense.

“I said, ‘I’ll lose my team if I do that. Let’s let him show he commits to me by losing 30 pounds. If he does that, I’ll go up some on the minutes.’ I played guys who deserved to play. I didn’t hand out playing time. You earn your playing time.”

In the book, Whitsitt reiterates it wasn’t his decision to acquire Kemp:

“Paul felt so badly about how the Shawn trade turned out for the Blazers that he wanted to publicly admit he had insisted on the deal and that I had argued against it. He didn’t think it was fair to me to take the blame for a bad idea I had tried so hard to talk him out of. But ultimately, I convinced him to let me remain the lightning rod. A lot of guys wouldn’t have done that, because their egos are so big. We’ve all got egos, but I’ve always felt my ego needs to stand down when it’s time to protect my owner. It’s just part of the job. Try to give your owner as much credit as possible when things are going well, and when things don’t go well, make no excuses, take responsibility and focus on moving forward.”

What a guy.

Whitsitt compiled his rosters like a rotisserie-league GM: Collect as much talent and let the coach worry about chemistry.

“Coach Dunleavy would talk reporters’ ears off about how his job was a losing battle with too many stars clamoring for more playing time than there were minutes to distribute,” Whitsitt writes. “The Oregonian once ran a story headlined, ‘The Toughest Coaching Job in the NBA.’ … moaning and groaning about ‘too much talent’ is like walking up to an unfinished painting, looking at it for a second and complaining it had too much blue. That might be true at the moment, but the artist has more work to do. Other colors are coming, and it’s going to be beautiful.”

At midseason during Dunleavy’s final season with Portland, Whitsitt signed Schrempf. Mind you, the Blazers already had Sabonis, Wallace, Davis, Kemp, Scottie Pippen and Stacey Augmon on their front line.

Says Dunleavy: “Bob says, ‘Would you like to have Detlef? I said, ‘I can’t promise him any minutes. That affects everybody else.’ Then he doesn’t even tell me he signs him. Somebody comes up to me one day before a game and says, ‘Det is in the locker room and he’s putting on a jersey.’ ”

Dunleavy says Whitsitt signed Schrempf with the agreement that he didn’t have to come to every practice. Dunleavy found out when assistant coach Tim Grgurich came to him saying the players were “irate” about the deal Bob had made with Schrempf. Dunleavy says he promptly called Whitsitt.

Dunleavy: “Bob, is this true?”

Whitsitt: “No, it’s not true. I told Det if he needs a day off to go talk to you, and see if you would give him a day off.”

Dunleavy: “Bob, I can’t do that unless it’s an emergency. It undermines what I’m trying to do with everybody else.”

Meanwhile, a few weeks later, Whitsitt signs Rod Strickland, adding him to a crowded backcourt that includes Steve Smith, Damon Stoudamire, Bonzi Wells, Greg Anthony and Pippen.

“I like having talent, for sure, but you have to have some role players, too,” Dunleavy says. “We had a lot of different personalities on that team.

“We’d have a meeting with our players at shootaround or practice after a game. I’d ask, ‘Who hates us this morning? Who didn’t get their numbers last night, even though we won?’ If somebody was unhappy, I ran the first two plays of the next game for that guy. You just had to manage people. It’s a part of what you do as a coach. It got difficult sometimes with that team.”

In the next-to-last regular season game against the Lakers in L.A., there were fireworks. A week earlier, Wallace had suffered a blackened eye after taking an inadvertent elbow from Sabonis. In the third quarter of the Lakers game, Sabonis was shoved by Shaquille O’Neal as they were going for a rebound. Sabonis, trying to draw a foul, flailed his arms and hit Wallace across the eye.

In the ensuing timeout, Wallace yelled at Sabonis as they approached the bench and threw a towel in his face, then walked away. Dunleavy then approached Sabonis.

“Sabas, do you want me to take care of it now or after the game?” Dunleavy asked.

“Coach, whatever you want to do,” he answered.

In the locker room after the game — a 105-100 Lakers win — Wallace was still furious, saying he was going to “F up” Sabonis. (Sabonis told reserve forward Antonio Harvey: “I will kill him.)” Dunleavy entered the room.

“Rasheed, you owe Sabas an apology,” Dunleavy said.

“Why would I owe the MF an apology?” Wallace asked.

“You just embarrassed him, and what he did was an accident,” Dunleavy said.

“He bloodied my mouth,” Wallace said.

“Either apologize, or I’ll suspend your ass, and it will cost you $50,000,” Dunleavy said.

“You can suck my d**k,” responded Wallace, who began to move toward the coach.

“I made a decision,” Dunleavy says. “I’d been in a lot of fights in my day. I would not have suspended him, because I was baiting him. Some guys jumped in to stop him and I said, “Let that big MF go. I’ve been coaching him for four years. I haven’t see that big MF hit anybody.” Rasheed turned around, headed for the shower and said, ‘I’m not falling for any of that Brooklyn s**t, Michael.’ ”

Wallace was suspended for the regular-season finale but not given an additional fine.

Dunleavy met with Whitsitt and said, “Bob we cannot let this happen without a huge fine as a deterrent.” Whitsitt, though, determined Wallace was needed for the playoffs. It didn’t help: The Lakers swept the Blazers 3-0 in the first round of the playoffs, and the season was over.

Dunleavy had one year left on his contract. He said he didn’t have a problem with “being a lame-duck coach” for the 2001-02 season. Whitsitt called him into his office. Here’s the way Dunleavy remembers their conversation:

Whitsitt: “Coach, we can’t extend you.”

Dunleavy: “I’m not worried about that. I want to coach this team out. We’re going to have a great season next year.”

Whitsitt: “I want to change your coaching staff. We have to fire two of your assistants.”

“I told him yes, but I was just calling his bluff,” Dunleavy says. “His eyes were blinking like crazy. I went back and told my assistants what he said, because I wanted to make sure they knew I was going to be loyal to them. Then I went back to Bob and told him I had changed my mind, that I wouldn’t do it.”

Dunleavy was fired, to be replaced by Maurice Cheeks.

“Just so everybody in the world knows this is the truth: May God strike down all my kids and grandkids if I’m lying about any of this,” Dunleavy told me. “I don’t know how much stronger I can say about what Bob has written. No. Total lies.”

Or, as one of Dunleavy’s assistant coaches with the Blazers puts it, “If you read the book, Bob gets everything right. Everybody else doesn’t.”

Dunleavy is retired now and living in New Orleans, where he is working on his second start-up company in the prescription medicine space. He retired from coaching in 2019 after a three-year college stint at Tulane.

For my money, Dunleavy was the best of the three head coaches during the Whitsitt era in Portland. Had Dunleavy been provided a more manageable group of personalities to work with, he might have won an NBA title. He came darn close, anyway.

► ◄

Whitsitt writes that in the fall of 2002, he let Allen know his ninth season with the Blazers would be the last.

“Paul spent the entire 2002-03 season in denial, either not believing I would follow through and actually resign or asking me what he could do to lighten my load, trying to get me to stay,” Whitsitt writes. “Paul wouldn’t give up hope that at some point, I’d give in and agree to stay.”

Whitsitt said he felt overwhelmed by trying to run two franchises plus his other duties.

“After I left the Blazers, they missed the playoffs for five straight years,” he writes. “They cycled through three presidents and four GMs and plummeted to last in attendance in the NBA. Paul tried to get me to come back — many times. I always said no. I had made my break and knew it was time to narrow my focus to the Seahawks.”

Allen is not around to confirm or refute any of this, of course. The Blazers’ fan base had eroded considerably in the final couple of years of Whitsitt’s run. I’m sure Allen was tired of hearing about the embarrassment the team had caused the city. I remember Allen saying at a news conference that he wanted the team to follow a new course in player behavior. Changing guard with the man running the personnel side of the franchise would seem to have made sense.

If you have always admired Whitsitt and want to hear his side of the story, this book is for you. If you believe that the former GM of the Blazers speaks with forked tongue, I would recommend reading just about anything else. You can guess which side I come down on.

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on X (formerly Twitter).

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.