Wooden to Casey: A legend follows a legend

It has been 50 years since John Wooden made a visit to the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity on the Oregon State campus and talked with its members for nearly three hours.

Hours later, on Feb. 24, 1973, Wooden’s No. 1-ranked UCLA Bruins edged the Beavers 73-67 before a crowd of 10,520 at Gill Coliseum. It was the 68th straight win over three seasons for the Bruins, who a month later would go on to beat Memphis State 87-66 for their seventh consecutive NCAA championship.

How did the Oregon State Sig Eps get perhaps the greatest coach in U.S. team sports history to take precious time on a game day to speak to them?

They asked.

Mike Cowgill was a Wooden and UCLA basketball fan and a dreamer. He wrote a letter to Wooden, congratulating him on his selection as Sports Illustrated’s “Sportsman of the Year” for 1972 and inviting him to speak at the SPE house when the Bruins were in Corvallis to play the Beavers.

Wooden, bless his soul, wrote back.

The return letter from John Wooden to Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity member Mike Cowgill in 1973 (courtesy Mike Cowgill)

“He said he wasn’t sure if he could do it,” says Cowgill, now 70 and an attorney in Albany.

Wooden told Cowgill where the Bruins would be staying in Corvallis — at the Towne House Motor Inn — and to check in with him at 4:30 p.m. on the day before the game.

“Doug Antone and I took his Mustang and got there just as they finished a team meeting,” Cowgill recalls. “He brought us in and we met all the coaches.”

“I think I can do this,” Wooden told the boys. “Come back in the morning tomorrow at 8:30.”

Said Cowgill: “Coach Wooden was a member of Beta Theta Pi Fraternity at Purdue. I believe his fraternity involvement while at Purdue was an important factor in his willingness to accept our invitation.”

Cowgill and Antone arrived at the Towne House on time the next morning. Wooden invited them into his hotel room and introduced them to his wife, Nell.

“Then we got into Doug’s Mustang and drove up Monroe to the (fraternity) house,” Cowgill says. “We got there at 9 a.m. and, with all the questions after his talk, it lasted til almost noon.”

Nearly 100 fraternity members and guests were in attendance.

“Coach Wooden talked about his ‘Pyramid of Success,’ his coaching philosophy, his mission to mentor young student-athletes to try to enrich their lives so they would become better students, better business people, better husbands, fathers and grandfathers,” Cowgill said. “It was a life-defining moment for me.”

Coach Wooden’s famed “Pyramid of Success”

In the 1990s, long after Wooden had retired, Cowgill wrote again to him and asked if he would send autographed copies of his “Pyramid of Success” for each of his children.

“He promptly did that,” Cowgill says. “I had them framed and gave them to my two sons on the day they graduated from OSU, and to my daughter when she graduated from West Albany High a few weeks after Coach Wooden died. They have them hanging in their homes.”

Another fraternity member on hand for Wooden’s speech that day, Jerry Hackenbruck, went on to coach 23 years of high school football at Madison, Lakeridge, Lake Oswego, Redmond, Mountain View and Summit.

“With that talk, Coach Wooden had as big an impact on my career as anybody had as far as coaching, teaching, working with kids,” said Hackenbruck, 69, now retired and living in Tualatin. “I was impressed with the humility he showed by doing that just because somebody asked him to.

“He had absolutely nothing to gain by it. He was talking to a group of people that had no impact on helping him have success for his program. He didn’t get paid for it. It wasn’t like we were an alumni group that might donate to the college, or people connected to players who could help him recruit. Nowadays, a big-time college coach would never take the time to do that.”

A Wooden-esque figure, however, would.

► ◄

To commemorate the 50th-year anniversary of Wooden’s visit, Cowgill and a group of SPE alums invited Bill Walton — the star of the 1972-73 Bruins — to speak to members of the fraternity. Walton declined.

So the SPE alums decided to ask the next-best possibility — Pat Casey, mastermind of Oregon State’s three national baseball championships and a man of legendary proportions in the state of Oregon.

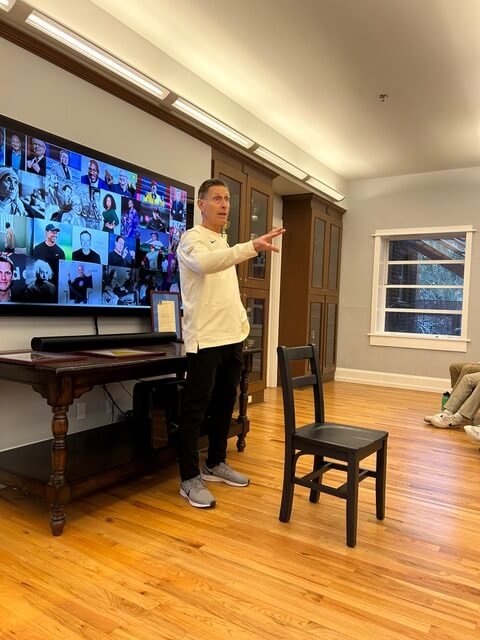

Casey emphasizes the pillars to success in his program while coaching at Oregon State: Honesty, trust, communication and relationships

Casey, now retired from coaching and working as special assistant to Oregon State athletic director Scott Barnes, said yes.

Wooden was 62 when he addressed the SPEs. Casey is 64.

Last Monday, Casey spoke to a group of about 75 fraternity members and alums in the same living room setting in which Wooden delivered his talk a half-century earlier.

Casey didn’t speak as long as Wooden. His talk was 35 minutes long, leaving another 25 minutes for questions. It was an hour worth taking in.

“I’m not a public speaker,” he told the listeners in self-deprecating fashion. “You’re going to have to hang with me. I’m intimidated being around a bunch of intellects, because I coach baseball guys.”

The reaction was laughter, an emotion evoked several times during Casey’s talk, which mixed humor with message. There were 50 undergrads in attendance, and they were in rapt attention throughout. I saw not one cell phone pulled out the entire hour, except one member taking photos. The young men were taking very seriously this rare brush with greatness.

Pat Casey addresses a full house at Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity at Oregon State

“We are so excited for this event,” house president Tony Butler-Torrez, a junior in business administration/political science, told me before Casey’s talk. “This is a great opportunity for our members. We also have potentially new members here along with (Interfraternity Council) executive members.”

Another member, senior Noah Evans, covers baseball for the OSU Barometer.

“This is Oregon State baseball lore,” Evans said. “Coach Casey is a legend. It is crazy to be able to share air with him. To hear his knowledge and how he was able to build Oregon State to the beast that it was in college baseball … I’ll be on the the edge of my seat.”

So were Evans’ fraternity brothers as Casey delivered a motivational talk.

“Something I say may inspire you to do something that you feel is difficult,” he told them. “We won championships at Oregon State with great people. You’re only as good as the people you surround yourself with. I want to talk to you about how I got to where I was and who helped me get there.”

Casey gave a short history of the early part of his coaching career following his release after playing eight years of minor league baseball in 1987. Married and with two young children, he returned to his hometown of Newberg and acquired a real-estate license. Then he accepted an offer to coach NAIA baseball at George Fox College.

“I made $3,000 the first year,” said Casey, who worked part-time in a pizza parlor and as a janitor cleaning gym floors to make ends meet. “I had my real-estate license, but I wanted to coach. The last three years, they paid me $6,000, so I made $30,000 in seven years — and I loved it.”

Oregon State came calling in 1994, and for a few years, the Beavers played against the likes of Washington, Washington State, Portland and Portland State in the NorPa. In 1999, the Beavers moved into the Pac-10. Many thought because of the weather and financial resources, the Northwest schools would never be able to compete with their southern brethren.

At first, the Beavers took their lumps. In 2001, they got swept in a three-game series at perennial “Six-Pac” power Stanford, losing the finale 22-5. Afterward, as he shook hands with Stanford coach Mark Marquess — who became a good friend — Casey saw an “I tried to tell you” look in Marquess’ eyes.

“I almost rolled over on the flight home,” Casey told the group. “I was thinking I did my guys an injustice. I almost quit. I almost gave in. When we got back I said, ‘No, we are going to change the way we do things. We are going to change everything about how we think.’ ”

Four years later, Oregon State was in the College World Series.

“The next year, we beat (the Cardinal) 15-0 to go back, and I got to shake (Marquess’) hand at home plate,” Casey said. “Pretty good handshake.

“Our mentality was, ‘You didn’t respect us. We’re Oregon State. We’re going to put our nose in your chest and move you all over the Sunken Diamond.’ ”

Work ethic was critical for Casey, who grew up one of seven children in his family.

“The best thing my dad (Fred Casey) gave me was nothing,” he said. “He worked hard. If I wanted something, I had to work. I learned how to work. When I came to Oregon State, I didn’t know how much work it would take to do the things I wanted to do.”

Casey spoke about desire and discipline and working to achieve goals.

“There is something in each of you that wants to be special,” he said. “Each of us has something unique in us that gets us to be the best version of ourselves. The reason it’s hard to find is because it’s hard to do. … dreams without action are nothing. It’s nothing unless you get your ass out of bed and do it.

“You have to be disciplined. There is nothing better than working hard and getting something. There is nothing worse than getting something when you don’t deserve it. When you have a dream and fulfill that dream because of the work you put in, that will fuel you for the next fire.”

People aren’t born equal, Casey said.

“The only thing we have that is 100 percent equal is time,” he said. “There are 86,400 seconds in a day, 168 hours in a week. If you sleep eight hours a day and live to be 75 years old, you’re going to spend a hell of a lot of time in bed. It’s what we do with the time we have that’s going to make you great. The No. 1 enemy to greatness is good. If you want to be great, you separate. Time is the No. 1 thing you have to manage.

“If you just take one hour a day and do something different, that’s 350 hours a year you conquer. You have to commit to it. We didn’t win championships necessarily because we were more talented than our opponents. We just knew how to take the talent we had and to a level they didn’t think they had until they believed in themselves.”

The pillars to Casey’s program at Oregon State: Honesty, trust, communication and relationships.

“You don’t have a relationship with somebody you don’t communicate with; you don’t communicate with somebody you don’t trust; you don’t trust somebody who isn’t honest,” the ball coach said. “Fear keeps us from doing great things. Fear paralyzes the human spirit. It divides the mind. It convinces us that we can’t do something we can do. It is the opposite of courage. Courage is the father of all great moments.

“It starts with work. You need a goal. I like short-term goals over long-term goals. If you ask somebody if they can lose 25 pounds in a year, they’ll say, ‘I don’t know.’ But if your goal is to lose two pounds in a month, everybody would raise their hand, right?

“Life changes when habits change. You don’t like what your past looks like and you want to change your future? Change your habits. Your habits become your character, and your character becomes your destiny. One of the most important things we can do is create good habits. Purpose moves people. You have to have a purpose. Purpose lets people think they have value.”

Leadership is integral to sports, but to other walks of life, too.

“Great leaders empower other people to become great leaders,” Casey said. “It is taking someone and convincing someone they can do something they didn’t think they could do. Great leaders create dreams. They create a bold vision and a road map of how to accomplish it. They are humble. They are service-oriented. They have to be fearless. They have to be smart. They have to live with an attitude of gratitude.

“Influence is one of the biggest things there is. You influence people around you every day. When one guy starts believing, you get another guy to believe, and he gets another. Then it’s pretty good. And when you don’t win, you jump back in the fire, because you’re not going to win every time.

“I love adversity, because teams are formed and leaders are found in times of adversity. It’s the first step toward success if we handle it right and use the pain we didn’t want to go through.”

Achievement, Casey said, can come at any stage of life.

“Tiger Woods broke 50 for nine holes of golf when he was 3 years old,” he said. “Anne Frank wrote her diary at 14. Bill Gates co-founded Microsoft at 19. Joe DiMaggio had a 56-game hitting streak at 26. Mother Teresa left the convent at 40, moved to the slums of Calcutta and captivated (the world) for five decades. Winston Churchill became prime minister of Great Britain at 64. Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa at 75. Ben Franklin invented the bifocal at 79. Dimitrion Yordanidis ran the Greece Marathon at 98. Ichijiro Araya climbed Mt. Fuji at 100. We are never too old. We are never too young. Don’t let anybody squash your dreams.”

It was time to conclude.

“You young people have an opportunity to do something great with your lives,” Casey said. “You are the ones who will be responsible for that. If you do it, it will be one of the greatest feelings you have in your life. Don’t settle for second place. Don’t let anybody convince you that you can’t do something you can do. There is unimaginable potential within each of us.

“I hope each of you guys reaches your potential, and values the people around you, and values your God-given gift of life, and lives it to the fullest.”

► ◄

There were questions from the fraternity brothers. In response, Casey told stories of the leadership provided by Mitch Canham and Darwin Barney on back-to-back national championship clubs, of looking up to his father and older brother Chris while growing up, of the impact his first-grade teacher had on him.

“Great leaders will influence more lives in one year than an average leader will in an entire lifetime,” Casey said. “Leadership is so important that an army of sheep led by a lion would defeat an army of lions led by a sheep.”

While coaching at Oregon State, “our guys had a belief system,” he said. “You cannot exceed beyond your belief system. If you don’t have that, you surrender. Don’t ever surrender, guys.”

And: “Life is about getting into your own soul and challenging yourself. … look at people who are doing something you want to do and find a way to do it better than them.”

And: “Inspiration is like my favorite beer — cold.”

That drew a roar of laughs.

Then the question: What’s next? Casey mentioned his foundation (called Soar4), in which he has raised money to feed the hungry, housing and shelter, medical assistance and educational needs. He is heavily involved with fund-raising for Canham’s baseball OSU program, which will build a $6 million hitting facility beyond Goss Stadium.

“I’ll go wherever I am led,” Casey said. “I look for special things to do. I wouldn’t mind being an assistant coach, just to be around players again.”

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on Twitter.

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.