Pros vs. Joes No. 15: Fast, athletic and smart —that sums up ‘The Fox’

(Editors note: Steve Preece, unfortunately, was unable to make his picks for the “Pros vs. Joes” Bracket Challenge.)

The odds of Steve Preece making it in pro football were not great.

The option quarterback out of Oregon State went unchosen in the 1968 NFL draft.

When he was signed as a free agent by the New Orleans Saints, they were asking him to play the other side of the ball.

Not only did Preece buck the odds, he played nine years in the league — five of them as a starter.

Preece made the conversion from QB to safety based on speed, athleticism and football IQ, traits that made him the perfect general for Dee Andros’ “Giant Killers” of the late 1960s at OSU.

Preece — who turned 75 last month — was raised in a Mormon family in Boise, the son of dairy farmers.

“My dad told me I could only play football if I did two things: Go to seminary and milk the cows,” he tells me during a recent conversation. “It was the biggest motivation of my life at the time.”

The fleet Preece was state runner-up in the 220-yard dash as a senior at Borah High with a best of 10.0 in the 100-yard dash. “I had a 9.7,” Preece says, “but they wouldn’t count it because it was on the Borah track. They weren’t sure it was long enough.”

Preece’s high school career was straight from a Hollywood script. As a senior, he was the All-State quarterback on an 8-1 football team (there were no playoffs in Idaho prep football back then) an All-State guard on a state championship basketball team and a key member of a state championship track and field team.

Oh yeah — he also dated the Homecoming queen. Hello, Chip Hilton.

“Ridiculous, isn’t it?” he says with a laugh. “A long time ago.”

Finalists for Preece’s services in football were Brigham Young, Colorado and Oregon State. He narrowed it to Colorado and Oregon State before choosing the Beavers. Preece was recruited by the staff of Tommy Prothro, who left for UCLA after the 1965 Rose Bowl game, just before letter-of-intent signing day. Prothro’s successor was Dee Andros, who came from the University of Idaho. He convinced Preece to stay with the Beavers.

Preece almost transferred after spring ball his freshman year. The returning starter at quarterback was senior Paul Brothers, who had led Oregon State to the Rose Bowl as a sophomore.

“I thought I outplayed the senior in the spring game,” Preece recalls. “I didn’t consider anything except how good I thought I was. I didn’t appreciate how good Paul was and what he brought to that team. I didn’t want to sit on the bench for a year. I decided to transfer to BYU. My family was all for that because of the Mormon factor.”

Preece went home for summer vacation. Two weeks into it, he called OSU assistant coach Ed Knecht — who had recruited him — and told him, “I think I might want to transfer.”

In those days, transfers had to pay their own way for a year of school.

“My family couldn’t afford that, and Oregon State knew it,” Preece says.

BYU officials had figured out a way to cover his tuition that wasn’t above board. Oregon State officials found out about it and were prepared to turn the Cougars in if Preece wound up in Provo.

“The played a little hardball with me,” Preece says.

Andros sent Knecht to Boise with a warning: “Don’t come back unless you bring back Priest (what he always called the quarterback).”

Preece came back.

“The whole episode changed my opinion of how much Oregon State was interested in me,” he says. “I’m very happy I didn’t transfer.”

It also allowed Preece to change his mind about Brothers.

“Paul became a good friend of mine,” Preece says. “He was like a big brother. He treated me like gold.”

Preece didn’t sit as a sophomore. He played often as a change-up to the more drop-back-style Brothers, running the bootleg or an option. Preece carried 34 times for 182 yards (5.4 average) and a touchdown for a team that went 7-3 and would have gone to the Rose Bowl if not for a 21-0 loss to Southern Cal in Portland’s Civic Stadium. Preece’s passing stats were lacking — 2 for 15 for 33 yards — but the 6-1, 195-pounder could really run.

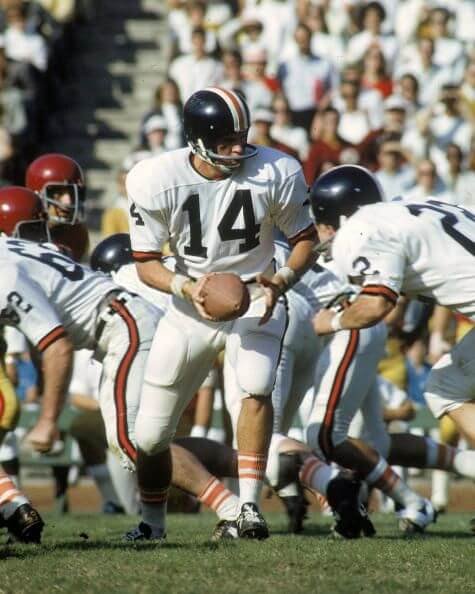

The 6-1, 195-pound Preece — his teammates called him “Fox” — was the perfect signal-caller for Andros’ Power-T offense over the next two seasons. He ran the show superbly, getting the ball to fullback Bill “Earthquake” Enyart and halfback Billy Main as the Beavers went 14-5-1, including the monumental 3-0 upset of O.J. Simpson and the No. 1-ranked Trojans in 1967. They just missed the Rose Bowl both seasons, losing to Washington 13-6 in ’67 and to USC 17-13 in ’68. Today, those Beavers would have played in a major bowl, but only the conference champion had that opportunity then.

Preece says players on both of those teams were unselfish and played for each other. He also gives credit to the seniors — the leftovers from the Prothro regime — players such as fullback Pete Pifer, wideout Bobby Grim, linemen Rockne Freitas and Skip Diaz.

“They treated us like teammates from the day we stepped foot on the field,” he says. “They set an example for the underclassmen. That’s how the team was built. That’s how the Giant Killers became what they were.

“We were a team that cared about each other, loved each other. Each guy was just as important as the next. It was a total team deal. (Center) John Didion and (defensive tackle) Jon Sandstrom were best friends. They were also in a fight about every other week.”

Preece encountered a “big transition” once he was signed by New Orleans.

“I hadn’t played defense since my sophomore year in high school,” he says.

Rookie camp lasted 10 days. He spent two days each at quarterback, running back, receiver, safety and cornerback. He was invited to training camp as a cornerback prospect.

During the preseason, Preece asked defensive coordinator Jack Faulkner how much not having played defense in college hurt him in the pros.

“It’s the best thing that could have happened,” Faulkner told him. “You don’t have any bad habits.”

As a rookie in 1969 the 6-1, 190-pound Preece was introduced to steroids — Dianabol to be specific.

“I did it for two-thirds of the season, and then they said it was enough,” he says. “They were giving me shots in the butt. It’s what everyone did. It was legal.

“And I kept eating. They gave me a jar of marshmallow stuff to eat whenever I was hungry. I got up to 216 and stayed there for the next 2 1/2 or three years. I never thought it hurt my speed, but it did. I got down to 190 with the Rams, and I could tell the difference.”

Preece played with losing teams in New Orleans, Philadelphia and Denver his first four seasons. He played in the secondary, was involved with special team coverage and served as holder for placekicks in all three places.

“I held for the last field-goal attempt of (former Oregon Stater) Sam Baker’s career in Philly,” Preece says. “He missed. I held for Tom Dempsey the next year and later with the Rams. He was best man in my first wedding and I was best man at his. I held for David Ray in Los Angeles when he was the Golden Toe Award in 1973.”

Preece scored his second NFL touchdown that year with the Rams as holder for a botched snap.

“The snap was high,” he says. “I grabbed it, and took it around the end and scored (from 11 yards out).”

Preece spent four seasons with the Rams from 1973-76, the first two as starting free safety. Those were some of the best teams of that era, with running back Lawrence McCutcheon and defensive stalwarts such as Merlin Olsen, Jack Youngblood, Fred Dryer, Jack “Hacksaw” Reynolds and Isiah Robertson. The head coach was Chuck Knox. The defensive coordinator was Ray Malavasi.

“The pass rush was phenomenal,” Preece says. “Every place else I played, you had to cover your guy for four seconds. Man-to-man, you were going to get beat sooner or later. You could never really be aggressive.

With the Rams, you’d count ‘one thousand one, one thousand,’ and the next step is the break to your receiver. We didn’t have to worry about double moves. I became a much better defensive back with those guys up front.”

The Rams had double-digit wins all four years for a collective record of 44-11-1 — and never got to a Super Bowl. They couldn’t get past the Cowboys or Vikings, who beat them twice each in the playoffs.

“The second one with Dallas, we got down quick, then came back and made it a game,” Preece says. “On a third-and-long play, I go up for a pass to Drew Pearson, and we’re both close to the ball. I catch it, (Rams teammate) Eddie McMillan hits me, the ball pops out, Drew catches it and goes for an 83-yard touchdown.”

Preece enjoyed playing for the Hall of Famer Knox.

“Chuck was a quiet guy,” Preece says. “With me, all he had to say was, ‘Hey 2-0, you didn’t play as well last game as you should have. You’ve got to be better.’ I’d be in a panic for three days. He knew how to treat everybody in a way that they responded. A marvelous coach and a great guy. He had so many great sayings — Knox-isms. Like, ‘He who lives in hope dies in s—t.’ ”

Preece finished his career in Seattle in 1977, playing under Portland native Jack Patera, with ex-OSU assistant Sam Boghosian as the offensive coordinator. His teammates included a young Jim Korn and Steve Largent. Preece started all 14 games and had a career-high four interceptions. During the last game of the season — on what proved to be the last play of his career — Preece suffered a concussion that had him laid out on the field for almost 15 minutes. But a knee injury is what ended his career.

In a story for the Portland Tribune in 2017, Preece told me he estimates he had 23 concussions during his football career. Here is the story:

But Preece believes he is one of the lucky ones (think Steve Young) who has had little or no cognitive impairment. He has been tested three times by NFL medical staffers and has been told is “normal for my age. I feel pretty good about it.”

Preece has kept busy since his retirement from football at age 30. He joined a commercial real estate brokerage in Portland in 1971 and founded Preece and Floberg (with Oregon State grad Bill Floberg) in 1980. They got into commercial real estate development in 1986. Preece is still working, though he has cut back to four clients that represent national chains, all retailers: TJX companies (Home Goods, Marshall’s, TJ Maxx and Sierra Trading Post), Petco, Wendy’s and Floor and Decor.

Steve’s avocation is broadcasting. He began serving as game analyst for Oregon State games in 1989 and did it for 23 years. He still is commentator on Beaver pregame and halftime radio broadcasts and is able to offer insights because of his relationship with the coaching staff.

Preece served on the selection committee that hired three straight head coaches — Mike Riley, Dennis Erickson and then Riley again.

“That’s the best thing I was ever involved with at Oregon State,” he says. “I feel really good about that.”

Preece underwent double bypass surgery in 2011 and had a Pacemaker inserted a year ago.

“It’s been awesome,” he says. “Before, I was really feeling pooped. My heart was down to 35 to 40 beats a minute. It took about two months to get the right balance. I’m feeling good now.”

Steve and wife Karen have been married for 25 years. Between them, they have three children and five grandkids. One of the kids is Nick Hess, 36, who is running on the Republican ticket for governor of Oregon.

Steve Preece and his wife of 25 years, Karen (courtesy Steve Preece)

“Nick’s a businessman who got fed up with how things are being run in Oregon,” Preece says. “He thinks he can help. He’s not the favorite, but he’s working hard, going all over the state. It’s hard to not be a political person and run for office. We’re incredibly proud of him.”

Preece has agreed to be a celebrity picker for the “Pros vs. Joes” Bracket Challenge, forecasting winners in the NCAA Basketball Tournament. He’s not a veteran of such things.

“First time,” he says, smiling. “I’m going to have to spend some time researching the damn thing.”

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on Twitter.

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.