Huber’s is more than just a restaurant — it’s a Portland institution

Huber’s Cafe has not been around since the coin flip that determined that the City of Roses would be named Portland and not Boston. It only seems that way.

The beginnings of Huber’s can be traced to 1879, when businessman Louis Eppinger opened a bar in downtown Portland he called “The Bureau Saloon.” Frank Huber was hired as a bartender in 1884 and became a partner in 1887 and sole owner the following year. In 1895, the name was changed to “Huber’s”; the business was moved to its current location at SW 3rd and Stark in 1910. A year later, it came under the management of Jim Louie, whose story we’ll soon tell.

Huber’s namesake Frank Huber circa 1905

Today, going on 150 years since its inception, Louie’s great nephews — James and David — own and operate the longest-standing restaurant in continuous operation in the metropolitan area, and possibly in the state of Oregon.

Huber’s owners James and David Louie

Maybe one million Spanish coffees and three million turkey sandwiches and dinners since it all began, the Louies are still running one of the best eating and drinking establishments in town.

“When I reflect on how long our family has been involved with this business, it makes me realize that being a part of Huber’s is more than just a job,” James Louie says. “It’s our family heritage.”

Today, Huber’s is a Portland institution, alongside such as landmarks Washington Park, Pioneer Square, the Old Church, OMSI and Voodoo Donuts. It’s a remarkable story of longevity, perseverance and excellence.

I have been a Huber’s fan and customer since shortly after I moved to Portland in 1975, and as I have gotten to know James through the years, my admiration has grown. Thanks for being our latest sponsor, James and David, and for allowing me the chance to retrace an important piece of the area’s history that should not be forgotten.

► ◄

Twenty years after Oregon gained statehood, “The Bureau” made its debut on the corner of 1st and Morrison in downtown Portland. Portland’s population in 1879 was 17,500. Horsecars for transportation were a recent phenomenon, with electric lighting still seven years away. A new fire engine house was built on Front Street in 1880, stabilizing the downtown district and enticing businesses. The arrival of the transcontinental railroad would change the city’s dynamics, attracting blacks who took jobs as porters and dining-car waiters. Through the 1880s, the city’s population more than doubled.

Also coming were Chinese emigrants, who by 1890 constituted more than 10 percent of Portland’s population. Most of them were young, single men who sent money home to their families. (Chinese women arrived in smaller numbers.) Many middle-class white women raised four to six children while supervising young servant girls and perhaps a male Chinese servant.

In 1890, Portland had the nation’s second-largest Chinatown to that of San Francisco. Some Chinese immigrants operated businesses, but many were common laborers — laundrymen, dishwashers and cooks, drawn by the prospect of prosperity as well as the desire to leave the poverty and political instability of southern China.

But there was an anti-Chinese sentiment in the Northwest at the time, especially during a short-lived depression in the mid-1880s. The Oregon Constitution denied Chinese-Americans citizenship, and there were sometimes violent antagonisms of one segment of the working class against another. White workers feared Chinese laborers threatened their livelihoods. In 1886, a group of men in nearby Oregon City expelled about 50 Chinese workers. The following year, a gang of thieves murdered 34 Chinese miners in Hell’s Canyon in eastern Oregon.

Also in place was the Chinese Exclusion act of 1882, the first law to deny naturalized citizenship to a specific nationality in the U.S. It was not to be repealed until 1945.

Entering this scene was Jim Louie, born in 1870 in Guangdong (Romanized as “Canton”), China, given name Louie Wei Fung. (Once he emigrated to the U.S., he felt he needed an American name.)

Huber’s patriarch Jim Louie with his serving staff in 1930

In 1881 at age 11, Jim arrived in Portland as a stowaway on a clipper ship from China. Shortly thereafter, his uncle, Sam Louie, arrived from France, where it was said he “learned to cook the French way.” Sam worked for a French family migrating to Oregon. Upon arriving, he conscripted Jim and instructed him in French cooking.

In 1891, Frank Huber hired Jim as chef and to work the “free lunch” counter. The Bureau was among a staple of saloons during this period that gave steady drinkers free meals in exchange for their business. (The theme was “beer for a dime, and have something to eat with it.”) Anyone who ordered a cocktail got a free turkey sandwich and a ramekin of coleslaw.

Affable and now able to speak English well enough to communicate, Jim Louie quickly became a popular figure. During the flood of 1894, he took to a rowboat behind the counter at “The Bureau,” as customers rowed up to pick up a meal.

In 1910, Huber’s made the move to Third and Stark, which at the time was located in the newly built Railway Exchange Building (a six-story edifice later renamed the Oregon Pioneer Building). It was the first fully concrete building in Portland.

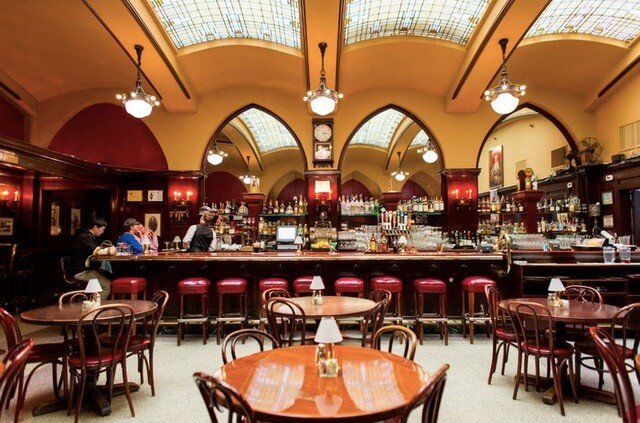

The interior was grand, with solid Philippine reddish brown mahogany paneling, a terrazzo tile floor and an arched stain-glass skylight. The arches on the west side of the room would come to remind customers of scenes from the World War II-era movie “Casablanca.”

Alas, Frank Huber did not live long enough to enjoy it. He died of heart disease in 1911, and widow Augusta assumed ownership. She immediately hired Jim Louie as manager. He still cooked in the morning but also moved to Frank’s position behind the bar while retaining authority over the roast turkey.

The place was still officially “Huber’s,” but to many Portlanders it became “Jimmy’s.” It was considered the afternoon club of the business district.

When Prohibition hit in 1920, Huber’s nearly closed its doors. But a delegation of Portland citizens urged Jim and Augusta to stay in business by selling the slices of turkey it had previously been serving for free, and the landlord offered easement on rent.

The establishment was converted to a restaurant, with roast turkey as the house specialty, but also expanding the menu to include ham, steaks, veal, lamb chops, pork chops and seafood. During Prohibition, it also operated as a speakeasy, covertly serving Manhattans in coffee cups.

Jim Louie had bottles of liquor in the kitchen. If you needed a drink to start your lunch off, and he knew who you were, he could set up you up with a martini.

In 1939, writer Frank Taylor of Collier’s Magazine visited Huber’s and wrote a profile on Louie, calling him “a Northwest institution” and, at 69 years old, “ageless.” Taylor wrote of visitors coming from the likes of New York, San Francisco and St. Louis to “hunt up this obscure hideout with its $17,000 worth of mahogany.”

Jim Louie, carving his patented turkey dinner as depicted in Colliers Magazine in 1939

For 40 years, every day except Sundays, Jim had cooked one to 10 birds “to a brown, not counting several thousand geese, ducks, wild fowl and Virginia hams,” Taylor wrote.

Every fall, Jim would personally inspect, buy and place in cold storage at least a thousand young turkeys weighing 20 to 25 pounds each. “Don’t buy cheap birds,” was the secret according to Jim, who had a special recipe for stuffing that included ham, oysters, chestnuts, celery and bread crumbs.

(“We use a similar recipe today, but without the nuts,” James Louie says.)

Jim’s propensity for cooking turkey didn’t happen overnight, wrote Taylor, quoting Jim in his broken English:

“A young fellow, he cook 100 turkey and know nothing. He cook 1,000 turkey and know not very much. He cook 10,000 turkey, and he know a little bit. Cook 50,000 turkey, he know something about it.”

So there you have it. Jim Louie was at 50,000 turkeys in 1939, and counting. And he knew plenty about cooking them.

If you’re curious about Jim’s private life, it’s complicated. Between 1920 and 1939, he made four trips to China, and got married on the first visit. But he “raised a family that couldn’t come to the U.S,” as one report put it. Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, he was never able to bring his wife, son or two daughters to America.

“Eventually, I met Jim’s son, and his grandsons came over from China on a student visa,” James Louie says. “They got their degrees in engineering from Oregon State. They both now live in California.”

In 1940, after the death of Augusta Huber, Jim formed a partnership with John Huber, Frank’s son. Shortly thereafter, John sold his half of the restaurant to Jim for a dollar and was remembered by the Louie family as being “generous and kind.”

In 1946, when Jim — or Jimmy, as he was called by so many — died while helping clean the bar, it was front-page news in The Oregonian. He was 76.

“It wasn’t from anything he ate,” James says today. “He may have had a heart attack. He had finished his work day and was feeling dizzy, so he laid down on a bench. All the crew had gone except for the dishwasher, a Chinese native who didn’t speak any English. He didn’t know how to call to get help. When the crew comes in the next morning, the dishwasher was here with Uncle Jim, who had passed away.”

► ◄

Jim Louie had three younger brothers. One of them was Hugh Louie, who emigrated to Portland in the late 1890s. Hugh was the grandfather of James and David Louie, co-owners of Huber’s today.

Hugh Louie was a pastor in Portland for a few years, then became the first person of Chinese ancestry to graduate from the U of O Medical School. He had two children, including Andrew Louie, the father of James and David. When Andrew was very young, his mother died. Hugh Louie moved back to China, where he served as personal physician for a government official. He took Andrew and his sister with him and quickly remarried. James says the children didn’t get along with their stepmother, and Hugh sent them back to Portland to live.

Andrew Louie graduated from Portland’s Lincoln High and attended Reed College for a period of time but got his pharmaceutical degree from the University of Detroit. Because of racial discrimination, Andrew could not get a paying pharmacy job in Portland.

“My father got hired at Frank Nau’s pharmacy,” James says. “After a couple of weeks, he inquired about when was payday. He was told, ‘You’re not getting paid. You’re working for the experience.’ ”

Andrew Louie led a peripatetic life for about a decade, bouncing from Portland to New York to Cleveland to Detroit and finally to Washington, D.C., before moving to China in 1937.

Andrew met Amy while both were college students in Peking, and they were married there in 1938.

“My dad was a kind, gentle person,” James says. “My mother recognized that right away. When he popped the question, she said yes quickly.”

Andrew returned to Portland in 1941 when their daughter, Lucille, was 9 months old and soon began work with his uncle Jim at Huber’s. Amy and Lucy stayed behind.

Amy, who had graduated from Peking Union Medical College, served as a pharmacist department head under the Chiang Kai-shek regime in China, directing 31 workers in the national health administration. It took Amy and her daughter four years to join Andrew in Portland. After the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1945, two of the first to enter the U.S. under the quota established with repeal were Amy and Lucy.

“My mother would go weekly to the U.S. consulate to try to gain entry in the U.S.,” James says.

Finally, their passports were approved. They flew from Chungking to Calcutta and then Bombay, from where they boarded a ship for the U.S. The ocean voyage was 34 days.

After Andrew and Amy reconnected, they had two more children — James, born in 1946, and David, born in 1952. James was born months after the death of his great uncle Jim.

In 1945, Andrew joined Jim as co-owners of Huber’s and became sole proprietor after Jim’s death. Andrew and Amy served as owners from 1953 to 1990.

Andrew Louie, flanked by sons James and David Louie

Andrew Louie worked long hours. During his time off, he could often be found at Multnomah Greyhound Park or Portland Meadows.

“Dad didn’t play poker with the guys,” James Louie says. “He wasn’t that type of gambler. His passion was the horse and dog races. It was a diversion after being at work all day. We’d close at 9 and he would head out to Fairview.”

“Dad loved to gamble, and he loved to have a little something to drink every day.” David Louie says. “He studied the dog charts. He would close the restaurant and drive out to Fairview and catch the last couple of races. Overall, he probably lost a little bit of money, but not to where it was hurting the family. It was just a fun leisure activity.”

As David got older, he would occasionally accompany his father to the dog tracks. David wasn’t a risk-taker. He would bet the favorite in a race to show.

“You’re not going to make anything betting that way,” his father would tell him.

“Dad was outgoing — a really nice man,” David says.

“Dad was very generous,” James says. “I needed a watch at one point and he had a Longines — an expensive watch. He took it off his wrist, gave it to me and bought himself another.”

Their mother, James says, “was a charming woman with a beautiful smile. She was a very determined person.”

“She was a hard worker,” David says. “She was a little tougher than our dad. She demanded respect. If anyone disrespected her, she wouldn’t tolerate that. People respected my mother.”

Amy initially was a stay-at-home mother.

“But one day my dad came home and said, ‘We have the bills coming in and we only have $50 in the checking account,’ ” James says. “Even though Mom had no restaurant background, she said, ‘I’m coming down to help.’ ”

Amy began as a cashier and host. Then one day, the lead cook at Huber’s “walked out on us,” James says. “She marched into the kitchen and started cooking. She had no training in commercial cooking, but she walked right in and took over. She participated in cooking seminars put on by Northwest Natural Gas. She didn’t have a huge repertoire of items, but what she did, she was good. She grilled razor clams to perfection.”

Huber’s menu, vintage 1941

By 1958, Huber’s was already the oldest restaurant in Portland under the same ownership and management. According to The Oregonian, it was a favorite luncheon place for the city’s businessmen — bankers, lawyers, judges, along with groups of women who convened there regularly.

Jim Louie was a popular, iconic figure in Portland, however, and his death affected Huber’s business. Through the 1950s and ‘60s, “it became a forgotten place,” David says. There were some lean years in the early 1970s, too. By then, it was time to begin to turn the business to a new generation of Louies.

► ◄

James Louie began working at Huber’s at age 14 in 1960. His first job was as cashier.

“My mother was from the old country,” James says. “She didn’t want anybody but family handling the money. Then I started waiting tables. When I was 21, I learned how to tend bar.”

James graduated from Benson Tech in 1966. He played outfield on the Engineers’ baseball team and took a ballroom dance class as a senior.

“That was my opportunity to meet some girls,” James says. “The only thing was, I was too shy to ask anybody out. On top of that, I didn’t have a car, and didn’t know how to entertain a woman. I’m not that good a dancer, either. I should have stayed on the ballfield.”

After his second year at Portland State, James felt he needed a break from the academic world. He went through training with VISTA, a domestic counterpart to the Peace Corps.

“But I got what they call ‘de-selected,’ ” he says. “Basically, I got cut from the team. And because I took a term off from school, that made me draft-eligible.”

In 1967, James was drafted into the Army.

“At least they wanted me,” he says. “I went willingly. But at that stage, a lot of my friends were against the war. They were conscientious objectors. I didn’t want to be an infantryman. I became a medic. I wanted to fix people, not kill people.”

He was part of the Army’s 82nd Airborne and was stationed in Fort Bragg, N.C., for two years during the Vietnam War. James ran the company aid station for a period of time. After his discharge, he returned to Portland. He took one term of studies at Portland Community College, another year at Portland State, then began working full-time at Huber’s in 1972 at age 26.

Until that point in his life, people had called him “Jim Louie.” Family called him “Jimmy.”

“They still call me Jimmy,” he says with a smile. “When I hit 50, I started putting ‘James’ on my business card. It had a little more impact. James Bond would not have been Agent Double-0-Seven if you called him ‘Jimmy Bond.’ ”

All three Louie children got their start working at Huber’s as youngsters. For years, after they took over the business in the late 1980s, Lucy, James and David were all one-third owners.

Lucy waited tables and served as a cashier beginning in high school. But it was not an easy life for the Louie boys’ sister.

“Lucy was diagnosed with schizophrenia, perhaps as early as sixth grade,” James says. “She spent some time at Dammasch State Hospital. They gave her electric shocks at one point.

“She came back in high school and did a couple of years at Portland State. She wasn’t dangerous, but sometimes she would say things that were bizarre or off the wall.”

Lucy never married.

“She was kind and gentle, much like my father,” James says. “Mom was maybe a little overprotective of her. During her adult years, she worked with the restaurant until the mid-‘80s. When my Mom became too old to work, Lucy retired along with Mom and Dad.”

Lucy died in December 2022 at age 81.

David’s first job as a teenager at Huber’s was “plating” ice cream and loading the Jackson dishwashing machine. In high school, he worked as a server. The father of a friend of his, Tony Huie, owned a Chinese restaurant.

“He wanted to work for us, so he started washing dishes at Huber’s and got me into it, too,” David says. “We worked together. We’d mop the floors and do what needed to be done.”

David graduated from Benson Tech in 1969 and then in liberal arts from the University of Oregon in 1974.

“When I was in college, I was thinking about getting into teaching,” David says. “My brother was already involved with the restaurant and asked me to come back to help out. I was still searching for what I wanted to do for a career.

“I’m a devout Christian. Some of my friends went into full-time ministry. I never got to that point. I came back to work part-time at the restaurant. One day, I was talking with one of our patrons. I told him I wasn’t quite sure what I was going to do. He pulled me aside, and said, ‘David, you have an established business here. You really should take advantage of this.’ ”

That hit home with David.

“And after awhile,” he says, “the business gets into your blood.”

From the point David came on full time in 1975, the brothers had a major voice in the business. In 1981, they became day-to-day managers. Andrew Louie died in 1989; Amy Louie passed in 1990. James, David and Lucy became owners in 1991 after the estate was settled.

► ◄

Huber’s went through what amounted to an identity crisis in the early ‘70s.

“We had become mainly a luncheon place,” James says. “Lunches last an hour, two hours. We didn’t do much evening business. One of my goals when I came into the business was to improve the evening business.”

Then lightning struck.

“It wasn’t due to my entrepreneurial genius,” James says. “It was an act of God.”

Since 1975, the signature item at Huber’s has been the Spanish coffee. For several years, the waiter theatrically pouring the drinks to customers was James Louie. The Huber’s name is now synonymous with the Spanish coffee flaming drink and James’ name is synonymous with its popularity.

According to American trade publication Nation’s Restaurant News, “James was the first tableside sensation at Huber’s.”

“That’s giving me too much glory,” says James, who got the idea when eating dinner with wife Helen — they were dating at the time — at the Fernwood Inn in Milwaukie. They were served a Spanish coffee tableside, featuring rum and Kahlua and topped off with whipping cream.

James brought the idea back to Huber’s, adding triple sec and nutmeg. And he developed a theatrical twist, using a match lit with one hand to light the 151 rum — and caramelize the glass’ sugar rim — then delivering the liquids to the glass via waterfall-like pours.

“One of our customers showed me how to light the match with one hand, and remove the match from the matchbook with one hand,” James says.

For about five years, James was the only Spanish coffee server at Huber’s.

“Our waiters were reluctant to do it because they were afraid they would set themselves on fire, which is a possibility,” James says. “If you put it out quickly, you won’t blister. I went to all-cotton shirts when I was working. You wear a polyester shirt and spill some flaming liquor on it, that shirt is toast.”

But the drink wasn’t going away, not with its popularity.

“Spanish coffees were real big for the health of our business,” David says. “People think of traditional turkey dinners more during the holidays. Spanish coffees are popular year-round. That made a big difference. James was very good and it got more and more popular. We started staying open later and were able to make more money.”

Alex Perez was a waiter at a neighboring restaurant and a regular customer of Huber’s who would often stop in to have a Spanish coffee. One day in 1980, he approached Louie.

“Jimmy, I want to come over and give you some competition,” Perez told him. “I want to make Spanish coffees.”

Perez quickly learned the art.

“Then customers asked for two at a time, and he made two with one pour,” James says. “Once he did that, they asked for three, and he mastered that. So most of the credit needs to go to Alex. He was the one who pioneered doing multiple Spanish coffees. All the guys doing their presentation today mimic Alex’s presentation.”

James learned to pour three at a time, too.

“At first I was a little envious of Alex gaining more popularity than me,” he says. “Then I realized, ‘This is a good thing. I don’t have to do them all anymore.’ Eventually, Alex became the main Spanish coffee guy.”

Perez worked at Huber’s for 20 years, until he left in 2000.

About the time Perez began, John Pierce began working at Huber’s. Pierce had been a boiler operator at West Point before choosing to move West.

Today, 43 years later, Pierce, 72, still works at Huber’s a couple of days a week.

“When I started, I didn’t know the difference between gin and bourbon,” he says. “But I learned, and I learned how to make a Spanish coffee. It comes with the territory. As a bartender, it’s just what you do at Huber’s.”

At first, Pierce would spend two days a week behind the bar, and two days on the floor making Spanish coffees. He watched Perez’ emergence as a pseudo-celebrity.

“He was a big personality,” Pierce says. “There were a bunch of other great bartenders who I learned from. The hardest part was getting used to being in public and developing the ‘people personality’ to handle it. I’m not a big personality person. I just come to work. When you’re pouring, people say a lot of things to unnerve you. You have to be a standup comedian on your feet. It’s a survival instinct.”

It took awhile to get the word out. When Spanish coffees were still a new thing at Huber’s, the Louies got some help from KINK radio personalities Scott Carter and James McGowan, who were customers.

“Would you like to have a little more business, Jimmy?” Carter asked.

“That would be great,” James told him.

Says Louie: “Scott would be getting off the air and Jack would be coming on, and Scott would say, ‘Hey Jack, I’m going down to Huber’s for a Spanish coffee. They’re the best.’ That was the start of it.”

Clark Gazzola displays his Spanish Coffee pouring talents

Before long, Huber’s was being called the “Buena Vista of the North,” referencing San Francisco’s Buena Vista Cafe, the birthplace of Irish coffee in the U.S.

In 1984, bar sales represented 50 percent of total volume at Huber’s and sales averaged 200 Spanish coffees a day.

There is no instruction handbook or training camp for making them.

“The more established bartenders train the rookies,” James says. “It’s like Michael Jordan in basketball. His coaches were responsible for 20 percent of his skills. The rest of the expertise on the court came from hours in the gym. Same with Spanish coffees. Instruction is a small part. The rest is doing it over and over.”

Back in the ‘70s, James says, those who made Spanish coffees at the Fernwood Inn “did kind of a long-distance pour of the Kahlua. Our guys are a little more flamboyant.”

Because of the Spanish coffee’s popularity, Huber’s is the largest user of Kahlua in the state of Oregon, and one of the largest in the U.S.

Several other establishments in the Portland area today serve Spanish coffees, though few with the flair or expertise as the pourers at Huber’s.

“Usually they just do it at the bar, and they use our recipe,” James says. “There is a saying — plagiarism is the highest form of flattery.”

James says Huber’s has sold as many as 600 Spanish coffees in one day. The average, he says, is about 250 daily.

The business has changed since the days of Andrew and Amy Louie.

“When my parents were running the restaurant, they would make maybe $15 a day in liquor sales,” James says. “A highball was a dollar; a beer was 50 cents. They would serve somewhere between 15 and 30 drinks a day. One of my goals when I went full-bore was to get the bar business going.

“Today, we’re at about 60 percent sales from food, 40 percent sales from liquor, which is a good thing from an insurance standpoint.”

Signature items today includes roast turkey, baked ham and Great Uncle Jim’s specialty coleslaw. The menu also offers three steak selections, nine seafood entrees and five pasta dishes. The turkeys are hormone-free and minimally processed. Organic field greens are used in the salads.

Huber’s had never had television sets at the bar. But when things were going well in the 1990s, the Louies did opt for some entertainment.

“On weekends, we would fill the place, plus have a line,” James says. “That’s not such a bad thing, but people would tell me they would drive by, and if there was a line, they would keep on going. I came up with this idea of providing entertainment for people waiting in line.”

Huber’s hired a magician, Matt Singleton, who was billed as “The Amazing Mathias.”

“He would do some magic for guests waiting in line,” James says. “And he could juggle. He did it for us for two or three years. We actually had three or four magicians work for us after Matt. They would come into the restaurant and work the room.”

► ◄

The interior space that today is Huber’s old dining room (also called the old bar or the historical section), is pretty much intact from 1910 and is designated as a historic landmark with the National Register of Historical Places. Capacity is about 100.

The “old bar” at Huber’s today

The stained-glass skylight, the light fixtures, the Philippine mahogany paneling and the terrazzo floor are original from 1910. Above the bar hangs an antique clock that dates to that era. The brass ship’s clock above the door was a gift to Frank Huber when he moved to the current location. The large brass cash register, still intact on the back bar, was purchased by Huber on August 4, 1910.

The pewter wine bucket and its silver wine stand, presumed to be a gift to Huber during the early 1900s, have been part of the restaurant since. The brass fans in the corners go back to the 1920s. Many of the bent wood chairs are vintage 1940, and three chairs are more than 100 years old. The beer steins in a display cabinet are antiques, including some that date to 1880, all a part of Huber’s private collection.

In 1997, the Louies doubled their space by opening 1,700 square feet of dining room area toward the SW 3rd Street side — with windows.

“The newer room’s space was previously a liquor store,” James says. “It was convenient. I would slide our order under the door and Bob and Carol would fill the order.”

The kitchen is adjacent to the new dining area. Downstairs is 500 square feet for a prep area, where the turkeys are roasted.

“We needed the larger kitchen,” James says. “It was amazing that Uncle Jim was able to crank out the amount of food he did with the limited space he had. Older people like (the new) space because it’s quieter. Everybody else likes the old bar. That’s the side that has the history and character. It’s the vintage part of the restaurant.”

The Hi-Lo Hotel bought the building seven years ago. The Louies lease their space. They have never considered moving.

“We have been here for so long,” he says. “We were among the first tenants in a building that was built in 1910.”

James is president of the corporation. David is vice president.

“It has nothing to do with being smarter or anything,” James says. “It’s just because I’m the older son. The way our responsibilities are divided up, I’m in charge of the liquor portion of the business, he’s in charge of the food portion of the business.

“And David takes care of the plumbing. He was able to fix that dishwasher when it went on the fritz.”

“The switch would burn out,” David says. “You had to buy a new switch, rewire it and boom! It would work.”

“If something is not working, he’ll give it the old college try to fix it,” James says. “I admire that. He’s willing to roll up his sleeves and get in there and try.”

The Louies are two peas in a pod. Both are mild-mannered and soft-spoken. Both Louies speak deliberately, putting thought into each sentence.

“They work together beautifully,” says Roxanne Lau, a dining room manager who has worked at Huber’s as a server for more than 20 years. “And they are delightful guys. They are very caring — great to work for.”

“When I first got involved in the business, sometimes we’d have conflicts over what to do,” David says. “We went to a counselor to try to resolve the conflicts. My brother being older, and he is the president, she said, ‘If he screws up, it’s his fault. You gotta go with what he says.’ ”

Truth be told, they make most of their decisions together. The Louies carpool to work together, arriving at Huber’s before 11 a.m.

“I live in Beaverton and David lives in Hillsdale,” James says. “His house is on the way.”

Both wear a coat and tie; James is particularly natty with his attire. In 1998, he was honored as Portland’s Restaurateur of the Year.

Owner James Louie is a dapper sort (courtesy Stephanie Holladay)

“It was very flattering,” James says, “but there were other restaurant people who were more deserving, like my presenter, Doug Schmick, and Bill McCormick.”

As a boss, James says, “I’ve learned a lot. One of the best things I ever did was start to delegate. If you try to do it all, things fall through the cracks. By delegation, you spread out the responsibility and less things get forgotten.

“We have two dining room managers — Roxanne and Stacy Ruff. They do a great job, and it’s a relief not to have to close the restaurant every night.”

The pandemic of 2020 and ’21 had a lasting impact on restaurant business throughout the country. More people order takeout now, which means less revenue for the restaurants.

“Sales are improving,” James says. “We’re still not profitable. Even though sales are higher, so are our costs. Products have gone way up. Labor prices have gone up. It is harder to get staffing. We had to raise wages in order to attract employees.”

But they have treated employees well, which inspires loyalty. Several workers have been with Huber’s for decades.

“They have treated me like family,” Pierce says. “I’m proud to have been with Huber’s so long.”

The Louies have helped inspire loyalty from their customers, too.

Craig Kirkeby has been coming to Huber’s since 1978.

“I used to work at Amtrak, and it was on the way home, so the convenience factor was nice,” Kirkeby says. “But I’ve become pretty good friends with Jimmy. Well, it was Jimmy at first. Then it was Jim. And now, I guess, it’s James. He has always been friendly. He is very good at remembering names. He shakes hands with everybody. He’s a calm person. I knew his parents. I’d sit at the bar and talk to his mom about China.

“I haven’t had a Spanish coffee in 10 to 15 years. I usually have a shot of whiskey and a beer. Occasionally I’ll order some to-go food — a cup of soup and turkey. It’s a comfortable spot. That’s why people go.They like being there.”

Ken Riddle and his wife have been coming to Huber’s since 1985.

“After the first time, we came back a week or two later, and James remembered our names,” Riddle says. “Being a young kid from a small hick town in Idaho, that made a great impression on me.

“It’s such a great place. No matter what, if you’re sitting at the bar, you’ll meet somebody from around the country, or around the world. Not a day goes by when I’m in there that I don’t start chatting with someone. I don’t know what it is about the place, but it seems to bring that forth. I like to watch the eyes of people who are first-time Spanish coffee drinkers. The look on their faces when (servers) are making them tableside is priceless.

“The architecture in the dining area is amazing. I always sit at the bar to the left, looking at the arches on that west wall, the skylight with the stain glass. It never gets old.”

In 2000, scenes for a movie titled “Men of Honor” featuring Robert De Niro, Cuba Gooding Jr., and Charlize Theron) were shot at Huber’s. Riddle was working as a grip on the rigging crew.

“We had to make a grid for lighting on all those beams that run east to west,” he says. “I didn’t want to be the guy to do any damage to such a beautiful structure.”

The Louies do an excellent job with customer relations.

“When a customer is not happy with their experience for whatever reason, we take it personally,” James says. “We don’t just blow it off and say ‘Too bad.’ We do our best to fix things.

“Having been married for 47 years (to wife Helen), I like to think I know how to apologize. There is a book called ‘The One Minute Manager.’ The authors write that if Nixon would have just apologized to the American people instead of authorizing a coverup, he probably would have been forgiven.”

► ◄

For one family to be involved in a restaurant business for more than 130 years is something close to miraculous.

“I like to say, they survived two pandemics,” Roxanne Lau says with a laugh.

“I believe that God had a hand in keeping our business going,” James says. “When I first went full-time in the family business, I took a long walk and I prayed. I said, ‘God, help me make a success of the business.’

“The result was, God showed me how to make a Spanish coffee. It wasn’t like Moses going up to Mount Sinai and seeing the burning bush. I didn’t go up to Mount Tabor and see a flaming Spanish coffee.”

James, 77, and David, 72, are beyond the age of retirement. How much longer will they run the business?

“David would like to retire in a couple more years,” James says. “Uncle Jim died right here at the restaurant. In my younger days, I thought I’d be like Uncle Jim, that they would have to carry me out of here. But I think I am ready to pass this on to my kids, if they are interested.”

David and wife Cindy have no children. James and Helen have three sons — David (45), James (43) and Tim (39). The oldest two have some interest in taking over the business at some point.

It’s possible that the Louies could eventually sell, or even shutter the business.

“I keep telling him if they ever close down, please let us do a big Casablanca night,” Lau says. “The old Huber’s menu, the old Huber’s cocktails, and we’ll go out in style.

“The place has been a big part of my life. I’ve met most of my friends and the people I love there. I always tell James, ‘You’re good at picking people.’ If they keep going, I hope it stays in the family. It has been a huge part of my family for two decades.”

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on Twitter.

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.