Fronk was one of Oregon’s great athletes, ‘and the kind of person to match’

Bob Fronk was easy-going, smart, inquisitive, competitive and, among other things, one heck of an athlete.

Most of those traits are indisputable, especially the last one, as those who watched Fronk — who died in Portland Thursday at age 62 — play sports in the late 1970s and early ‘80s.

Fronk, however, was not lucky.

A little more than a year ago, Bob — who was never a smoker — was diagnosed with lung cancer. After treatments, the cancer was in remission for a short while, but it returned. His oncologist told him he had six months to a year to live, according to brother Jim Fronk, five years his senior. At his assisted living center on Thursday, caretakers checked on him in his room after missing a couple of meals.

“He was gone,” Jim Fronk says. “No autopsy will be done, but they feel it was some sort of cardiac event.”

I met Bob when I was a whippersnapper reporter with The Oregon Journal, fresh out of college and covering a lot of high school sports. He was a star athlete at Sunset High, where he had the good fortune to play for a pair of outstanding coaches — Don Matthews in football and John Wyttenberg in basketball.

Sunset Apollos (from left) Todd Frimoth, Bob Fronk, Stan Walker with coach John Wyttenberg

As a sophomore, Bob was a member of the 1975 team that won the state AAA basketball championship. As a junior that fall, he quarterbacked the Apollos to the state AAA football championship, then did it again in 1976, the second time marshaling a team that went 12-0. I covered both of the football title games and several of Bob’s basketball games during his junior and senior seasons. According to basketball teammate Kevin Bryant, Fronk went out for track on a lark his senior year and long-jumped 21-7.

Bob Fronk (left) with teammates Todd Frimoth and Stan Walker, holding the 1975 basketball state championship plaque

“Bobby was a really good athlete,” Bryant says. “One of the best Sunset has ever had.”

Yes, Fronk was a stud, and an awfully nice guy. I got to know his father, Bill Fronk, president of Hyster, who had no big shot in him despite being decided a big shot.

Bob was recruited for both football and basketball — a little more heavily for football. He visited Nebraska. All four Northwest Pac-8 schools wanted him for football, basketball, or both. He wound up at Washington, where both Don James (football) and Marv Harshman (basketball) sought his services.

Basketball won out, though Fronk — 6-4 and about 195 — did participate in spring football after his freshman basketball season in 1978, competing against the likes of Tom Porras and Tom Flick for quarterback duties. Fronk decided it would be too hard to play both sports in college, so he opted for basketball, and had a terrific career with the Huskies.

Taken by Indiana in the sixth round of the 1981 NBA draft, he survived until the final cut with the Pacers. Fronk then played two years professionally in Germany before beginning a career mostly in education.

In recent years, Bob and I had reconnected. We talked and emailed regularly and met for happy hour occasionally near the Lake Oswego hotel in which he resided for awhile. He seemed to have a fascination with the news business in general and newspapers in particular.

“He was a news fanatic,” says Brent Green, his childhood friend and football teammate at Sunset.

“Bob would loved to have had your job,” Stan Walker tells me. Walker, a 6-5 forward with an excellent shooting touch, was a two-time Oregon Player of the Year who went on to become a four-year starter at Washington.

“He had a real curiosity and quest for knowledge about current events,” says Walker, who lived with Fronk one year off campus at UW. “All I wanted to do was play ball. I wasn’t that polished on world events. He was always very interested in that stuff. When he lived with me, he subscribed to six newspapers — the Seattle Times and P.I., The Oregonian and Oregon Journal, USA Today and the Wall Street Journal. There were newspapers everywhere. I can’t believe how much reading he did. The Internet was made for Bobby. That made it easy for him to get all the information.”

Green grew up on the same block as Fronk.

“We did everything together as kids,” says Green, who was one year ahead of Fronk in school. “All we did was sports. We played football in the park and basketball in my driveway. We put lights outside so we could play into the night. It was a fun experience being around him.”

Fronk wasn’t always a quarterback.

“In Pop Warner, he played the line, and he was one of the toughest guys on the team,” Green says. “He wasn’t the biggest guy, but he had a built-in toughness. He would just beat people up, especially on defense.”

As a sophomore at Sunset, Fronk was a starter — at cornerback. He also punted for a team that went 3-6.

The next year, running Matthews’ veer offense, Fronk started at quarterback as the Apollos, who suffered regular-season losses to Beaverton and Jesuit, then shot through the postseason unscathed, beating Milwaukie 35-14 for the title.

“He fit in with our clan pretty easily,” Green says. “Bob was super competitive. He didn’t want to lose at anything. He was a really good leader. He wasn’t the most talkative guy, but he ran the show. He had a heck of an arm on him, too. It came naturally to him, but he also put in a ton of time working on it.”

“Bobby took a back seat to the seniors, even though he was a leader by example,” says center Rusty Shackleford, who was a year ahead of Fronk in school. “He was quiet, heady, smart. Our nickname for him was ‘Puttering Bob.’ He just puttered around. He walked around the halls at school with his shoelaces undone. You’d go into a PE class, he’d already be there, bouncing the basketball while reading the paper.

“He was an excellent quarterback, though. He used his arms and his legs, and also his head. In the huddle, he took command. Early in our semifinal game against North Eugene and Danny Ainge, we were all excited and talking on the field. Bobby yelled, ‘Shut up! Get in here and listen up.’ ”

In the third quarter of the championship game against Milwaukie, Fronk took a hit out of bounds on Civic Stadium’s hard artificial surface.

“He got his bell rung,” Shackleford says. “There was no concussion protocol at the time. He went out for a series, then returned and ran for a touchdown on an option play. After we kicked off, we were standing on the sidelines. He said, ‘Shack, did we score?’ I said, ‘Yeah, and you’re the one who scored.”

Though he was a star, Fronk didn’t act like it.

“There wasn’t anybody who didn’t like him,” Green says. “He had an easy-going personality. Loved to laugh.”

The next season was even better. Sunset went 12-0 and edged Forest Grove 14-7 for its second straight state title. Fronk was honored as a first-team All-State quarterback and played in the Shrine Game that summer on a North team with another QB of some repute — Neil Lomax.

Fronk drives for a basket in a Metro League game as teammate Scott Hacke (31) and Beaverton’s Brian Hilliard look on.

At Sunset, Fronk played varsity basketball as a sophomore and junior with teammates mostly a year older than him.

“We poked a lot of fun at him,” says Todd Frimoth, a starting forward during Fronk’s sophomore and junior seasons. ‘He was just excited to go on a road trip as a sophomore. We’d tease him about it, telling him, ‘This isn’t the NBA.’ He took it well and was a lot of fun. He was such a great guy.”

Bob Fronk (right) with Greg Everson, point guard on Sunset’s 1975 state championship team

“Bob had the skills and athletic talent to play up a class,” Walker says. “He was a really hard-nosed competitor. If he sensed he had an advantage over you, the kill shot came in. If he had somebody on the ropes, he’d put 30 on them. He was relentless. Not everybody has that skill. He was really tough. That made him a good football player, too. He didn’t think there wasn’t anything he couldn’t do. When the opposition was back-pedaling, he got more aggressive.”

Sunset’s state championship team of 1975. Fronk is No. 34

“Bobby was a unique player in the Wyttenberg system,” Frimoth says. “We called his position ‘top circle,’ which was essentially the point guard, normally a non-scoring position in the system. But Bobby was never shy to shoot the ball, and he was so talented, he found a way to score.

“He was creative in the way he played, and Coach Wyttenberg let him (create) and wanted him to. It made a huge difference in that position and opened up a ton of stuff for everybody else, including Stan. He redefined that ‘top circle’ position for us.”

Scott Hacke was a starting guard as a senior and played on the ’75 state championship team at Sunset.

“Bob and Stan were such elite athletes,” Hacke says. “The thing that made us special is they were teammates to the core. They brought the rest of us up beyond what we would have been able to do because they expressed the confidence in us.

“Bobby loved to shoot. I got to start as a senior because I was a defensive specialist. If I were a shooter, I’d not have broken into the rotation. Stan and Bobby were going to take the bulk of the shots.”

Fronk had to adjust his game, though, to fit into Wyttenberg’s system.

“Frankly, Bob was selfish as a player when he was young,” Hacke says. “He’d hog the ball and he would shoot. He wasn’t going to pass much. On any other high school team, he’d be the guy the coach would want to have the ball in his hands, but we had Stan. Bob had to seriously modify his game to adapt to our system. But he saw the big picture and did what we needed him to do.”

Like many youngsters of that era, Fronk wore his hair long. He emulated two of his basketball heroes, “Pistol Pete” Maravich and Geoff Petrie.

“He wore floppy socks like Pete,” Hacke says. “He’d scrunch them down to the shoes like Pete did. His tongue would be twisted as he was driving past somebody, just like Pete.”

Like Fronk, Bryant attended Petrie’s youth camp at Pacific University.

“Bob was just in love with Geoff,” says Bryant, a starting guard on Sunset’s state championship team. “He played his game like sort of a combination of Pete and Geoff. Long hair, floppy socks, tongue out all the time.”

Hacke attended some basketball camps with Fronk, too.

“Bobby was not the guy to bunk with,” he says. “During the afternoon break after practices, he’d take his socks off and leave them wherever they landed. There was nobody to pick up after him. We would laugh about that aspect of him. There was always a mess in his wake.”

During Fronk’s junior year, Sunset was undefeated in Metro League play and went into the state tournament as a favorite, but was knocked out in the first round by a Mark Radford-led Grant team. The Apollos won the consolation trophy, but it was a disappointment. Wyttenberg retired after the season and assistant Joe Simon took over coaching duties. With most of the talent departed, Sunset didn’t make the state tournament. Fronk had a prolific season, though.

“He was such a fierce competitor,” Bryant says. “As a senior, he played against North Eugene (in the regular season). There’s a photo of him driving on Danny Ainge. It was like, ‘I don’t care who you are, I’m going to do what I do.’ Very confident, but low-key. Despite all his success, you’d never know.”

Bob Fronk drives for a basket against another player of some repute, North Eugene’s Danny Ainge.

“He was such a great athlete,” Hacke says. “He had a lot more to brag about than he ever did. He wasn’t one to toot his own horn.”

The Eugene Register-Guard’s All-State team, arguably the greatest collection of talent in the state’s history. Fronk played at Washington, Ainge at Brigham Young, Radford, Blume and Stoutt at Oregon State.

Fronk was a first-team All-State selection as a senior in 1977, joining Ainge, Radford, Parkrose’s Ray Blume and Lake Oswego’s Jeff Stoutt. I consider it the greatest class in the state’s prep basketball history. Ainge went to Brigham Young and Radford, Blume and Stoutt to Oregon State, where they were keys to the Beavers’ “Orange Express” teams that rose to a No. 1 national ranking in 1981. Ainge, Radford and Blume went on to play in the NBA.

“I believe Bob felt minimized in that class of ’77,” Walker says. “I sensed he felt he was considered a tier below the other guys. He followed me (to Washington) because he felt he could have the same kind of success. He wanted to get away from any comparisons to the other guys.”

As Fronk’s senior year at Sunset ended, the Trail Blazers won the NBA championship. Hacke’s father, Al, was a photograph at KPTV. Scott, now a freshman at Mount Hood CC, would sit courtside with his dad and shoot video for fun. For the deciding Game 6, he was able to get his friend Fronk a press pass. Fronk sat on the baseline next to Hacke, watching the game.

After the game, Fronk wandered with a crowd of media into the Blazers’ locker room and was witness to a raucous championship celebration. There’s a photo of him standing directly behind Bob Gross as the Blazer forward drinks a beer and laughs it up.

As a senior at Sunset High, Bob Fronk finagled his way into the post-game locker room scene and had a “Forrest Gump” moment after the Blazers clinched the 1977 NBA championship. That’s Fronk the left of Bob Gross (30) and Dave Twardzik.

“The guys all call it a ‘Forrest Gump’ moment,” Hacke says with a laugh. “I call it ‘Zelig’ after a Woody Allen movie in which he inserts himself into all these historical scenes.”

Fronk wasn’t an immediate hit at Washington. As a freshman, playing behind Don Vaughn and Mike Neill in the backcourt, he averaged 4.7 points while shooting .465 from the field and .833 from the free-throw line.

As a sophomore, playing behind Vaughan and Lorenzo Romar, Fronk averaged only 3.4 points while shooting .419 and .630.

“The sophomore year was a tough one for Bob,” Walker says. “Coach Harshman wasn’t giving him a lot of time. Bob’s stints were short, he was starting to struggle, and I was concerned he’d get pigeon-holed. I admired how he stayed with it.”

Harshman gave Fronk an opportunity to start his junior year and he ran with it. “He had a fantastic season,” Walker says. “It was a pivotal moment in his athletic career.”

With Romar setting up things in the backcourt, Fronk averaged 11.0 points while shooting a sterling .601 from the field and .797 from the line. It was Harshman’s best team during that span — 18-10 overall and 9-9 for fifth place in the Pac-10.

“There are scorers and there are shooters,” Walker says. “Bob was a great shooter, but he was more of a scorer than a shooter. Romar was a pass-first guy. He made the guys around him better. Bob could put up points on people if they didn’t concentrate on defending him.”

With Walker gone for Fronk’s senior year, Fronk took on an even bigger role. Starting with Vaughn in the backcourt, he averaged 16.7 points while shooting .504 from the field and .813 from the line.

After nearly making the Pacers, Fronk played two years professionally in Cologne, Germany. That experience opened a door to the world to him. He returned to the Seattle area and in 1983 married college sweetheart Julie Silke, with whom he had a son, Joe. (Bob and Julie divorced in 1990). After a few years coaching high school basketball and a long career as a counselor, Fronk went abroad to serve six years in guidance counseling for high school students making decisions about college — three in Belgium and three in Qatar.

“Bob was a private person, but intellectually curious,” his brother says. “That manifested itself in him taking those overseas positions. He had an opportunity to do a lot of side trips. He traveled a lot through Europe in those years.”

In 2017, Fronk retired and returned to Portland, living by himself in a hotel. He stayed connected to his Sunset classmates.

“We were a band of brothers,” Hacke says. “We remained that way all these years later.”

Frimoth and his wife taught abroad for 11 years.

“When Bob and I would meet for breakfast a couple of times a year, that was a lot of fun to talk about travel experiences,” Frimoth says. “It was completely different than reminiscing about old hoop days. That connected us in a much deeper way, which I really appreciated.”

Hacke, who has served 34 years as a game camera operator at Blazer games, shared Fronk’s love for smooth jazz.

Bob Fronk loved smooth jazz in general, and Grover Washington Jr. in particular.

“George Benson, Grover Washington Jr., the Crusaders,” Hacke says. “In recent years, he’d send me links to songs, like some long-form sax solo.”

Sports was always a suitable topic, too.

“All the years we didn’t see each other, we would have our banter back and forth on Husky and OSU sports,” says Green, who attended Oregon State. “You could poke fun at him and he’d poke back.”

When Fronk and I got together, we discussed a variety of things. He was writing a book about Dick Crews, the first black basketball player at Washington, and asked a lot about the process of book-writing. We talked about his son Joe, now 32 and a talent agent who lives in Southern California. He was very proud of Joe and flew down to visit him several times since retirement.

Basketball was always a welcome subject.

“He loved the game,” Hacke says. “He loved it more than Stan and Kevin Bryant, and those guys love the game.”

Fronk’s death has hit hard among his friends and former teammates at Sunset.

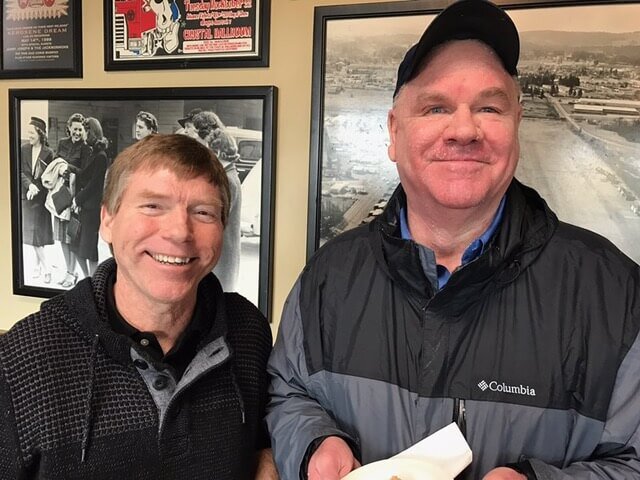

Bob Fronk (second from left) with former Sunset teammates (from left) Scott Hacke, Rusty Schackelford, Todd Frimoth and Kevin Bryant

“I have shed more tears over Bob’s passing than when my own parents departed,” Shackleford says.

I’m hopeful this column will remind people how special Bob Fronk was.

“Truly one of the great athletes to come out of the state of Oregon,” Walker says. “And the kind of person to match that.”

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.