Four books that might catch your interest this summer …

(To make it easy for you to buy any of these books if you are interested, I have embedded links to buying each book on bookshop,org. I do get a commission if you use the links in this post.)

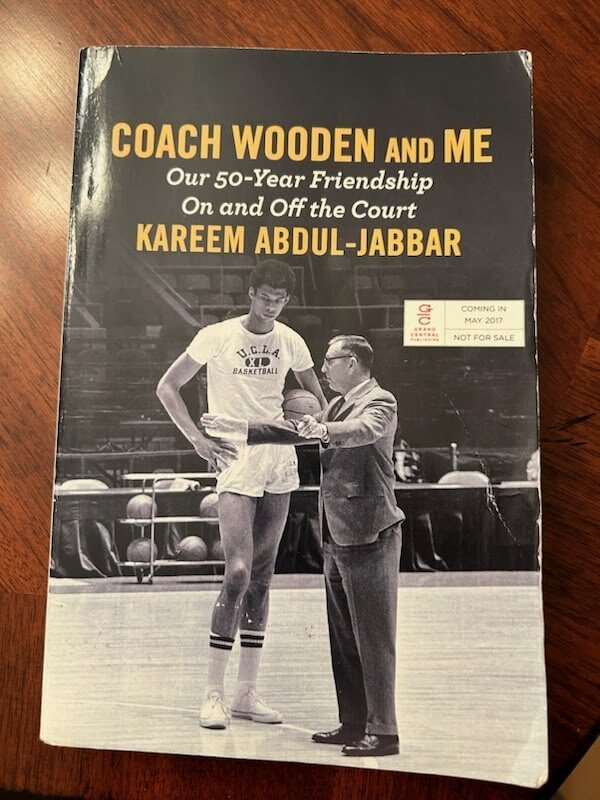

Coach Wooden and Me: Your 50-Year Friendship On and Off the Court

By Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

HarperCollins Publishers

Grand Central Publishing

This book was given to me by my wife, who saw it on a free library shelf. It is paperback, and at first glance I thought it was a vestige of Scholastic Book Company, which sold books via order forms through schools during my childhood in the 1960s.

Then I took a closer look. It was published in 2017 when Jabbar was 70 — a half-century after he played for John Wooden and led UCLA to three straight NCAA basketball championships.

And oddly, this particular book is a review copy, sent out to media before the finished product is released for sale to the public. I have received these books on occasion. No photos, no final copy editing of the manuscript. “Not for sale,” it says on the cover, and for good reason. There were a number of errors, but I cut slack to Jabbar on this, trusting that he made the necessary edits in the final product. It led me to wonder, though, who the recipient of this book could have been. And how could it wind up in my hands?

The book is basically a love letter to Wooden. Like Bill Walton, Abdul-Jabbar idolizes his former coach, who died four months short of 100 years old in 2010. Kareem is careful to devote part of a chapter to Wooden’s “flaws,” including his role in clashes with Wooden — generally when the player bent or broke one of his from-an-earlier-era rules. So Wooden wasn’t a saint, but still a mild-mannered, genius of a coach who served as role model, mentor, father figure and friend to Kareem for nearly 45 years.

Their friendship evolved through three phases: 1, Abdul-Jabbar’s time a player for Wooden at UCLA; 2, while he played for the Milwaukee Bucks, and 3, after he returned to Los Angeles to play for the Lakers. From that point until Wooden’s death, they spoke often via phone, had lunches and dinners together, and Kareem often visited him to watch sports or movies at Wooden’s home. Kareem was appreciative of the coach’s support as he transitioned to Islam in the early ’70s.

Abdul-Jabbar is a scholar and an excellent writer who has published several books, mostly on African-American history. I’ve not read them, but have read several of his essays, notably in Time Magazine. A deep thinker, he has much to offer in the area of literary persuasion, but the main motive here was to pay tribute to his favorite person on the Planet Earth.

Kareem’s coaching career was short and undistinguished considering his credentials as a player, in part because of his reputation as a difficult personality. I was tasked to interview him a few times when he was playing against the Trail Blazers in the 1980s and was struck by how sullen and uncooperative he was. Wooden had protected him from the media at UCLA, which I think works against the athlete in the long run. In the NBA, there are rules requiring players to cooperate.

In his autobiography, “My Life,” former teammate Magic Johnson could have been talking about me with the following anecdote:

“We’d be sitting in the locker room, right across from Kareem, when some innocent young writer from another city would start walking toward him … the reporter would go up to Cap and say, ‘Excuse me, Kareem, could I get an interview with you?’ Kareem wouldn’t even raise his head. Sometimes the reporter would put his hand on Kareem. Big mistake. Kareem would look up with those eyes. His book wouldn’t move, but his face would. He would look right through the guy. The next thing you’d see was the reporter backing up in fear.”

When Abdul-Jabbar cried on Wooden’s shoulder about difficulties landing a coaching job, “he would not indulge in self-pity,” Kareem writes. It might have been a matter of inexperience, the coach suggested. Or, as I suggest, perhaps karma.

Kareem also broaches the subject of being bothered for autographs, sometimes while eating.

“Coach was always gracious and friendly, making each person feel like a welcomed interruption of his otherwise bland day,” he writes. Kareem? Not so much.

The reader will be touched by the genuine affection conveyed by Abdul-Jabbar for a man who was different than himself in so many ways.

“Our legacy as friends would be one of the most important and rewarding accomplishments of my life,” Kareem writes. In the years before Wooden’s death, he says he felt as though “my last parent was dying.”

Of Wooden’s funeral: “We all went home that day knowing we had lost the gentle lion in all of our lives.”

► ◄

The Duke: The Life and Lies of Tommy Morrison

By Carlos Acevedo

Hamilcar Publications

This is the sad story of a small-town kid who became a big-time boxer and won the WBO world heavyweight championship in 1993. But Tommy Morrison was much more famous for his role as Tommy Gunn in the 1990 film “Rocky V.”

Acevedo minces no words in describing Morrison’s walk on the dark side of life, in which the protagonist proved to be part scoundrel, part scumbag.

“His talk of Bible-inspired morality never stopped him from drinking, womanizing and siring children out of wedlock,” the authors writes of Morrison. “Nor would scripture prevent a future of drug use, bigamy, divorce, domestic violence, racism, drunkenness and prison.”

Morrison was also a chronic liar who, 10 years after contracting AIDS, claimed he was the victim of false positives and was able to have two more professional fights (one in unregulated Mexico, one in lightly regulated West Virginia). He likely caught HIV from injecting steroids with a needle, or possibly sleeping with an infected woman.

Writes Acededo of the run-up to a Morrison-George Foreman title bout: “As usual, Foreman was stuck in PR mode, his default setting; almost nothing he said during his second life of boxing had any relation to the concept of truth. That was another trait he shared with Morrison.”

Tommy was born in Arkansas and raised primarily in Oklahoma. His father, Tim, was a low-life who had a sordid relationship with whiskey and women. He abused Tommy’s mother, Diana, who spent six months in jail after accidentally killing his mistress with a knife. (She was trying to stab him, but missed. She was eventually acquitted.)

Tommy and alcohol were an explosive mix, too. His wild and reckless lifestyle led him to getting AIDS in 1996, though he told friends he had tested positive as early as 1989. Wherever Tommy went, women trailed after him. “He was a womanizer beyond anything I’ve ever known,” trainer Bill Cayton said.

Tommy was once married to two women at the same time.

He also was a very good boxer, with a career record of 48-3-1, though much of that was the results of set-ups with tomato cans by his managing groups. (Morrison also was 202-20 as an amateur.)

Acevedo wrote that Morrison had heart as a fighter, with a signature left hook and box-office attraction as a “great white hope.” He was generous to his friends, benevolent with charitable events and personal appearances and donated some of his purses to his “Knockout AIDS Foundation” to help children with AIDS.

But as life went on, Morrison was in and out of jail for DUI and drug offenses. He spiraled downhill to his death at age 44 in 2013. Cause of death was listed as cardiac arrest, but it was undoubtedly the result of many years living with AIDs in his system.

The author runs amuck a bit with his similes (“Pierre Coetzer, a pallid South African whose frangible skin made a Dutch Masters box look like a Mosler safe.” … “Don King had been sued more often than Cindy Crawford had been photographed”). But this is a well-constructed, well-written book with no sugar-coating of Morrison’s interesting life and cautionary tale.

► ◄

By Larry Csonka

Matt Holt Books

Early in his autobiography, Hall of Fame fullback Larry Csonka promises to tell stories. Boy, does he deliver.

Csonka’s greatest achievement was being a member of the Miami Dolphins’ 1972 team that went 17-0 and won the 1973 Super Bowl. Give him credit, too, for writing a decent book about his life.

But I want to quibble with something Csonka writes. Several times, he calls himself a running back. Nope, he was an old-fashioned fullback — a 6-3 1/2, 240-pound freight train who gave blows as much as he received. Fullbacks today are blocking backs and occasional receivers. Csonka, the 1973 Super Bowl MVP, still holds the Miami Dolphins’ career rushing record with 6,737 yards along with 53 touchdowns.

“Zonk” tells plenty of stories on himself, such as pranking the mailman with a chicken in the mailbox as a kid, of having a dean call him on having schoolmate take a test for him at Syracuse (and he basically got away with it), of scaring away four would-be thieves from an auto lot with a shotgun when he was serving as night watchman in college.

Csonka was a tough guy, maybe the favorite of Don Shula of all the players he coached. Csonka tells the story of being bashed on the nose during a game against Buffalo.

Writes Csonka:

“When I ran to the sidelines, Dr. Virgin looked it and said, ‘This is going to hurt.’

“While our trainer, Bob Lundy, held my head, Dr. Virgin grabbed my nose with his hands and pulled my septum straight. Then he produced two stainless steel rods.

“ ‘This is going to hurt, too,’ he said as he shoved them both up my nose. I heard a crunch as the rods opened my nasal passages. When he pulled them out, it felt like my brain was attached to the rods. The blood started flowing.

“Next, he soaked a wad of gauze with something medicinal and stuffed it up my nose. It stopped the bleeding. And it deadened the pain a bit, too.

“I went back into the game.”

Csonka tells of a near-death experience with partner Audrey Bradshaw in 2005 in Alaska, where the outdoor-oriented Csonka has made his home for many years. On a boat journey to fish for silver salmon and hunt caribou, they got caught in a storm and were at sea for 17 harrowing hours before being rescued by a Coast Guard helicopter.

“At that moment,” he writes, “Audrey and I agreed we would never venture onto big waters again in a boat smaller than 35 feet.”

Csonka tells football stories, too, and much about his closest friend, halfback Jim Kiick, who died of dementia in 2020. There are some great photos of Csonka and Kiick as “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” their nickname during the glory years with the Dolphins.

There is plenty in this book, though sadly little about his former wife and children. Csonka pretty much ran to his own beat when the kids were young, once taking six weeks in the offseason to go to Vietnam to visit with troops despite his wife’s misgivings.

But mostly, it’s a fun read. Csonka’s journey to 76 years of age has been complete.

► ◄

By Lee Lowenfish

University of Nebraska Press

Red Murff. Billy Blitzer. Paul Snyder. Paul Krichell. Lou Magnola. Gary Nickels.

If you recognize even one of these names, you probably know a little too much about major league baseball.

These are several of the dozens of major league scouts profiled in this book about the craft of scouting by those who lived it in the era before analytics.

Major league “bird dogs” have been instrumental in the history of professional baseball dating to the early 20th century. Here we read about many of the scouts who found the uncut gems who turned out to be Hall of Famers, along with the many busts who never made it in big in The Show.

Murff, for instance, scouted for the Houston Astros, New York Mets and Montreal Expos over a 34-year career. He was credited with finding Nolan Ryan, Jerry Koosman and Jerry Grote for the Mets. Murff also missed on left-hander Balor Moore, a first-round pick of the Expos who finished 28-48 in parts of eight seasons through his MLB career.

These scouts got to know the players and their families personally and developed a feel for what a player needed to be successful. They weren’t always right, but neither are today’s analytics that project what a player’s physical dynamics are and will be, but can’t measure the size of the heart or the will to get the most out of one’s abilities.

I found it interesting how the scouts got their jobs and what made them successful. Most of them had professional baseball playing experience but none of them were stars at the major league level. Even the good ones didn’t make a lot of money as a scout, but some of them helped make the owners of their teams rich.

This book isn’t for every sports fan. But if you like baseball, history and underdog stories, it is a worthwhile read.

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on Twitter.

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.