Books I’ve read recently, for better or for worse

(To make it easy for you to buy any of these books if you are interested, I made each image linked to buying the book right on amazon.com. I do get a commission if you use the links in this post.)

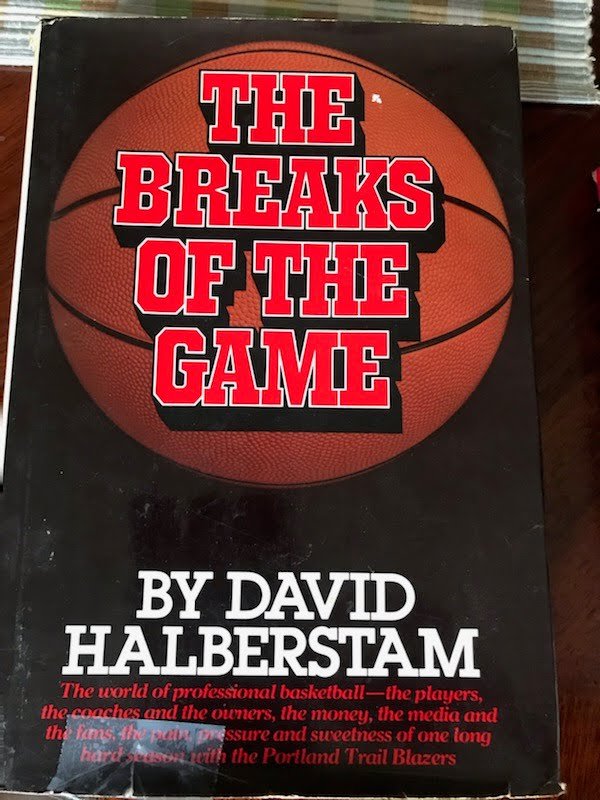

By David Halberstam

Alfred Knoff, Inc. (1981)

Noted author David Halberstam — with a Pulitzer Prize for international reporting already in his possession — took on an interesting assignment: Tag along with the Trail Blazers for a year.

The season was 1979-80, three years after Portland won its only NBA championship. Several key players from the title season, including Maurice Lucas, Bob Gross and Dave Twardzik, were in the final stages of their careers with Portland. Halberstam also got lucky with the debut of Billy Ray Bates, whose star shone in Portland for even a shorter time than Bill Walton’s.

I read this book soon after it was published, but 40 years later, had forgotten its essence. I was glad for the opportunity to re-read it and learn a lot of information that had escaped my mind.

Halberstam received unbridled access to the team primarily through three people — coach Jack Ramsay, assistant coach Bucky Buckwalter and Stu Inman, the director of player personnel.

It’s a great read if for no other reason that the almost unprecedented inside information Halberstam was privy to. He also provides a good deal of history of the first decade of Portland’s only major-league franchise, which began operations in 1970.

The author’s writing style is unusual. He uses few quotes, opting mostly for narratives while providing a series of vignettes that connect in one way or another. Rather than quoting a subject, he paraphrases what his sources evidently told him. The reader is led to believe what he is writing is the truth. A lot of time, I’m going to guess, it is.

Halberstam offered great information procured from the many hours he spent with Ramsay and Inman. He learned early in the season that the Blazers coveted New Jersey rookie Calvin Natt; they snatched him just before the trade deadline. They liked Kansas guard Darnell Valentine; they took him with the 18th pick in the 1981 draft. Another one: Ramsay had worked out a trade of Lucas to Chicago for the No. 2 pick in the draft during the summer of ’79, but owner Larry Weinberg nixed it.

After the ’77-78 season, the players had voted Ron Culp a quarter-share of the playoff revenue —and, wrote Halberstam, the vote came down along racial lines, the black players believing he had become Walton’s de facto personal trainer.

Another anecdote from early in franchise history is provided on a 1973 confrontation in the Blazer locker room (Halberstam calls it “the clubhouse”) between coach Jack McCloskey and star forward Sidney Wicks. Wicks: “I’ve checked you out and you’re nothing but a loser. You’ve been a loser every place you’ve coached, and I’ve been a winner everywhere I’ve played.” McCloskey: “All-star? Sidney Wicks an all-star? The only all-star team you could make is the all-dog team.”

Halberstam writes that in the summer of 1976, Portland and New Orleans agreed on a trade involving Wicks, but “after a very brief visit to which the New Orleans general manager (Halberstam doesn’t name him, but it was Barry Mendleson) expressed his extreme displeasure with Wicks and his personality, he was returned to Portland.” Before the next season, Wicks was traded to Boston for “marginal value.”

There is plenty on Walton, though he left the team after the 1977-78 season in controversy eventually filing a malpractice suit against the Blazers, doctor Bob Cook and trainer Culp. Walton was now sitting on the bench — injured, of course — with the San Diego Clippers. Not all of his teammates agreed with him on the subject.

“He only signed with San Diego because he wanted to come home,” said Tom Owens, the man who replaced him as the Blazers’ starting center, told Halberstam. “That’s OK, but he didn’t have to blame it on the medical staff.”

Walton blamed Cook and Culp for delivering painkillers to his left foot in 1978, after which he was diagnosed with a stress fracture.

“I’ve been back there when Bill was getting shots, and yes, I saw the needle,” Twardzik told Halberstam. “But no, I never saw the straps that held him down.”

The author also writes that, after he left Portland, Walton met with Ramsay. After the coach told the center he could not imagine a more complete relationship than the two had enjoyed with the Blazers, Walton nodded but said he could not go back, that Ramsay was too intense, too consumed with winning. Not sure about the authenticity of that one.

Halberstam got it right on Ramsay, calling the coach “an absolutely driven man. Every minute had to be used. Everyone was part of a search for excellence and for victory.”

The author had some interesting takes on Lucas, writing of the Pittsburgh native, “Portland as a city did not mean a lot to him. He had created a genuine niche and he was immensely popular … when he came on the court at the beginning of a game or when he collected a particularly important rebound, they had a special sound for him, a long, low cheer using his name, turning it into a veritable train whistle: “Luuuuuke.” He loved it … but Portland, he thought, was a very white city. Not much in the way of streets there. He liked to think of himself as a person of the streets.”

And: “Never for a moment did Maurice Lucas forget that Bill Walton was white and when then played together he made six times as much as Lucas did.”

Lucas, of course, returned to play his final season in Portland in 1987-88 and was twice a member of Blazer coaching staffs. He lived in the city through most of the rest of his life until dying from cancer at age 58 in 2010.

Race plays a major role in Halberstam’s book. Among his observations:

“Many of the black players, drafted involuntarily to this distant and alien timberland, populated as it was primarily by white people, came to love Portland. They loved Oregon because of its natural beauty, because it was an easy place to raise children and because they remained well-known long after they played their last game.”

This book was written the year after Magic Johnson and Larry Bird entered The NBA. It was a different era, the league struggling to gain its identity, dealing with drug problems from many of its players, unable to get even games from its championship series on live television.

Different financial times, too. In 1980, the Dallas Mavericks were purchased for $12 million. That couldn’t even buy an NBA starter anymore. Value of the Mavs today: $2.7 billion.

A quibble: There are no photos in the book to help illustrate the text. Really?

Portland staggered into the playoffs with a 38-44 record, to be the worst record in Ramsay’s 10-year run with the team. The season came to an end with a thud in a first-round playoff loss to the Seattle Supersonics: Writes Halberstam: “It was, after all, a long season for a troubled team in a troubled league.”

And yet, a book about that troubled team that is worth reading.

By Jack Ramsay with John Strawn

Timber Press (1978)

This book was published when Ramsay was at his hottest — in the months after he coached the Trail Blazers to their only NBA championship in 1977. (I wrote about how I obtained this copy of the book in a previous post on this website here.)

It’s a combination instructional/biographical book, only 174 pages long — and that includes several full-page photos. The first two chapters cover information about Ramsay’s young life and how he came to coaching along with how the Blazers of that period were pieced together. The last three chapters cover Ramsay’s thoughts on life in the NBA, officiating (he was an early proponent of adding a third referee, which finally happened in 1988), management and the draft and a brief synopsis of the championship season.

The middle chapters are Ramsay’s chance to offer his coaching philosophies, which have aged well through the decades since he wrote the book. He seemed very open to sharing his trade secrets, which included publishing a letter he sent to to Maurice Lucas in the weeks after the championship was won. Ramsay emphasized defense and loved the transition game, still key components to the NBA game. The biggest change has been the proliferation of the 3-point shot, which was introduced in 1979. I think Jack would have had mixed emotions about that, knowing how much he loved the post game and the passing game.

The book mostly ages well, though it was a different world then in many ways. Fines for being late to a team meeting were — I kid you not — $2 per minute. Prior to the first meeting of the season, Bill Walton got an $8 fine; Lucas and Herm Gilliam were docked $18 apiece. Even in a wholly different economic market, that seemed more than a bit light.

“Doctor Jack” was a cerebral sort who, along with ghost writer Strawn, put together a book any Blazer fan with an appreciation for history would enjoy.

By Łukasz Muniowski

McFarland & Company, Inc.

Near as I can tell, Muniowski didn’t interview anyone for this book, subtitled, “A History of the NBA’s Best Off the Bench.” The author merely collects information from previous literature about his title subject and fleshes it out to 146 pages.

Full disclosure: Muniowski carried several tidbits and excerpts from my book, “Jail Blazers,” and uses me for an endorsing blurb on the back cover. At that point, I hadn’t yet read the book.

The author provides a history of many of the NBA’s reserve players, and the evolution of the use of them, beginning with the start of the league in the late 1940s. He sometimes goes off on tangents and offers extraneous information that has little to do with the sixth-man role.

Errors in any manuscript are nearly unavoidable, but some of the ones in this book are of the head-scratching variety: “Warriors owner Al Attles” (he was the team’s general manager). … “Detlef Schrempf played at Washington University” (it’s the University of Washington).

The author — a native of Poland — includes discussion on players who mostly spent only the very early stages of their career as a reserve, among them Hall-of-Famers Clyde Drexler, Kobe Bryant, Scottie Pippen, Steve Nash and Tracy McGrady.

He would have been better to focus on players who either were known as true sixth men for at least a good portion of their careers (i.e., Schrempf, Frank Ramsey, John Havlicek, Kevin McHale, Bobby Jones, Ricky Pierce, Dell Curry, Manu Ginobili, Jamal Crawford, Lou Williams) and/or those who won the NBA’s Sixth Man of the Year Award (Bill Walton, Cliff Robinson). Personal interviews with as many as possible would have been advantageous. Find out what are the attributes they believe makes a good sixth man, the difference between starting and coming off the bench, etc.

But maybe that’s just me.

Going 15 Rounds With Jerry Izenberg

By Ed Odeven

Self-published

Odeven, according to the “About the author” notes, is “a veteran sportswriter based in Tokyo.” The book is about Izenberg, probably most famous for being one of the final two media members to cover each of the first 53 Super Bowl games, a streak that ended in 2020. Izenberg is a member of the National Sports Media Association Hall of Fame and, at 91 years young, still writes columns for the Newark Star-Ledger. He has written 15 non-fiction books and, at age 90, penned his first novel. A boxing aficionado, Izenberg developed a close relationship with Muhammad Ali, with whom is is pictured on the cover.

“From the days of Sugar Ray Robinson to Sugar Ray Leonard and beyond, Jerry Izenberg has been a gifted chronicler of the sweet science,” Odeven writes.

The author reached out to me wondering if I’d like a review copy, probably figuring since I’m an old-time sportswriter that I’d be familiar with Izenberg’s work. Truth is, I wasn’t. Though I knew who he was and would see him occasionally at major national events, I’ve never met him. I generally have known writers from the West much more than those from the East.

Even so, I’ve enjoyed reading many East Coast-based sportswriters through the years. Phil Mushnick, Peter Vecsey, Bob Ryan, Jack McCallum, David Aldridge, Shaun Powell, Ian O’Connor and Mike Lupica come to mind, the latter the only one of the group I don’t know personally. I’ve rarely read Izenberg, who comes from an earlier era, with contemporaries such as Dick Young, Red Smith, Shirley Povich, Dave Anderson, Edwin Pope and Jimmy Cannon. That was before my time.

I did go back and read Izenberg’s obituary of Ali, written in 2016. It was terrific. (You can read it here)

There are brief examples of Izenberg’s writings, but the book is primarily divided into two parts — the results of interviews with the veteran scribe, and reflections of mostly Eastern-based writers proclaiming their admiration for Izenberg as a journalist and person. If this interests you, I’m sure you can purchase a book at edodevenreporting.com.

► ◄

Readers: what are your thoughts? I would love to hear them in the comments below. On the comments entry screen, only your name is required, your email address and website are optional, and may be left blank.

Follow me on Twitter.

Like me on Facebook.

Find me on Instagram.

Be sure to sign up for my emails.